Ahead of the 2022 World Cup starting in Qatar, there will be a couple of weeks of football-related content on the blog. Football was a popular sport for working-class spectators in interwar Britain, alongside (greyhound) racing and motor sports. Some historians even credit the popularity of football with bringing diverse social and ethnic groups togethers as neighbours went to support their local teams.[1] By the end of the interwar period, football clubs at the top end of the league were almost completely populated by professional footballers; but there were also still plenty of amateur clubs which delivered players of a high calibre. League matches were usually played on a Saturday afternoon, as most workers finished their weekly shifts at lunchtime on Saturday.

At the close of the 1930s, the Daily Express decided to capitalise on the increased popularity of professional football by commissioning author Leonard Gribble to write a serialised murder mystery which featured the real-life players and staff of Arsenal Football Club.[2] After serialisation, The Arsenal Stadium Mystery was published as a book and a film version was made almost immediately; both appearing shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War.

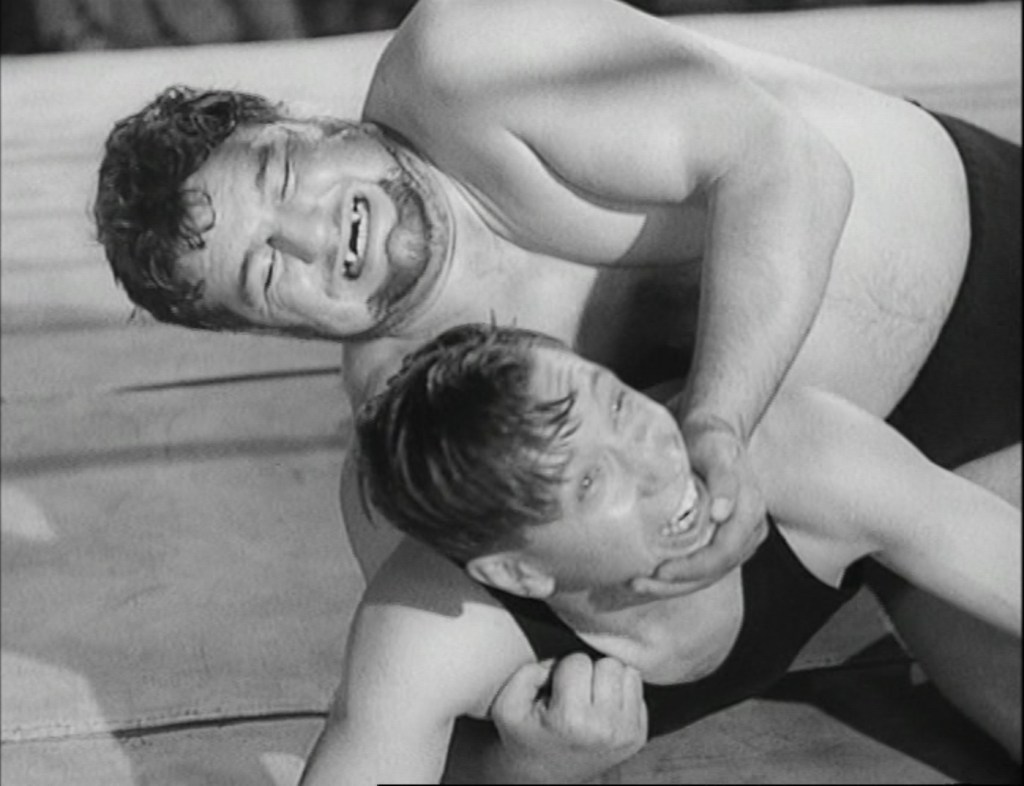

The plot of The Arsenal Stadium Mystery is fairly straightforward: Arsenal play an amateur team, the Trojans. During the match, one of the Trojan players, Doyce, collapses on the field and dies shortly afterwards. Scotland Yard are called in and conclude Doyce was poisoned; Inspector Slade methodically works through the possible suspects until the case is resolved. Although a number of Arsenal players appear as characters in the book (and the Arsenal manager, George Allinson, even got a speaking part in the film adaptation) they are naturally not implicated in the murder or its resolution.

The police investigation concentrates solely on the Trojan players and staff. The conceit of the football game provides the type of ‘closed circle’ which interwar detective fictions liked to use: a very limited number of suspects, a tightly controlled window in which the murder must have taken place; and limited ways in which the weapon could be disposed of.

Aside from the murder story, The Arsenal Stadium Mystery provides the modern reader with plenty of insight into 1930s professional football practices. Gribble was clearly given access to the Arsenal club players and grounds in the writing of the book – the parts of the stadium to which the public do not usually have access are described in detail. The rapid professionalisation of football is reflected in the vigorous training practices of the players: ‘The game to-day is faster than it has ever been (…) Only the fit can survive.’[3] Arsenal also apparently already had a youth academy set up, dubbed a ‘nursery’, to train up promising young players.[4]

When it comes to the game itself, Gribble provides a diagram reflecting the starting positions of both teams. Both Arsenal and Trojans are shown to play with five forwards, three midfielders and two defenders[5]; a formation that was much more common in the early days of professional football than it is today. The author also provides an almost play-by-play account of the match, in sections of the story clearly written with football-mad Daily Express readers in mind.

As well as details about the actual gameplay, Gribble pays substantial attention to convey the culture of football fandom. For example, he spends several pages describing the convivial atmosphere in the streets and train stations around the stadium after the match is over:

‘In the trains the corridors and entrance platforms are choked (…) The air is full of expunged breath, smoke, human smells, and heat. But there is plenty of laughter, plenty of Cockney chaff. Whatever happens, however great the discomfort, the crowd keeps its good-temper. This herded homegoing is just part of the afternoon’s entertainment.’[6]

Needless to say, this ‘entertainment’ is described as an innately masculine past-time. It would not be possible for women to enter this crush of human bodies. When Inspector Slade of Scotland Yard enters the story, he too enters in a social pact with the football players which excludes women. During his investigation, he questions one of the Trojan players, Morring, in front of a woman friend, Jill. Morring implies in guarded language that his fiancée, Pat Laruce, had had an affair with the victim, Doyce. Slade:

‘‘I take it you told him to be careful or next time he’d have more painful reason to regret his – um – interference?’ The two men grinned, while the girl looked from one to the other, wide-eyed, unable to appreciate a humour that was essentially masculine.’[7]

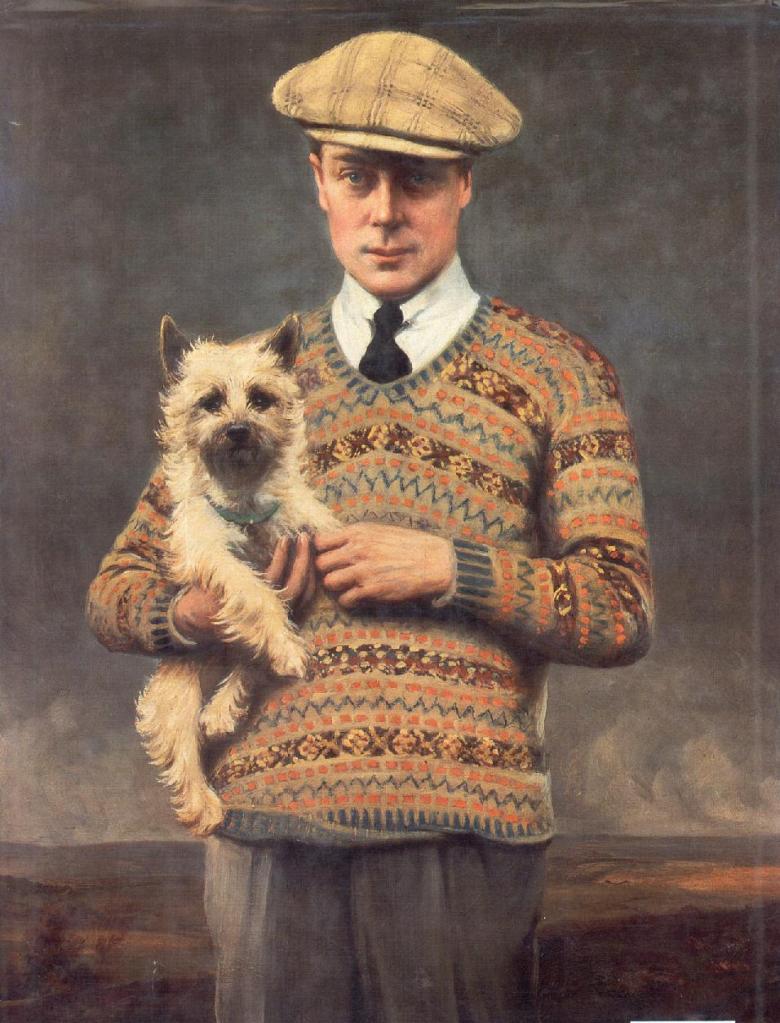

Phrases like this make it clear enough that Gribble was writing for a male audience; he also made the main female character, Pat Laruce, extremely unlikeable. Not only is Pat revealed as having cheated on her fiancé Morring, Gribble also portrays her as an extremely calculating woman who uses fake emotional outbursts to control men’s behaviour. He describes her as follows: ‘The daughter of a chorus girl who had married a publican after burning her fingers with a scion of the aristocracy, she [Pat] had imbibed her mother’s outlook on life.’[8]

Pat works as a model for advertisements; a job that entails her offering up her physical appearance for (male) consumption. Pat’s independence and modernity are unequivocally rejected by Gribble, and presented as intergenerational faults that are passed on from mother to daughter. There are several points in the book at which Pat is described as confused that her emotional manipulations are not working on men as she expects them to. Her friend Jill, by contrast, is presented as pure and innocent (as in the quote above which implies her complete ignorance about sex), and therefore a much more suitable life partner.

The Arsenal Stadium Mystery reveals much about the practicalities of professional football in 1930s Britain, as well as delivering a reasonably competent murder mystery story. It also carries its sexist gender views on its sleeve, by using the medium of football to promote a misogynist worldview in which professional sport is equated with male sociability.

The film version of The Arsenal Stadium Mystery (starring the real 1939 Arsenal squad) can be viewed for free on YouTube.

[1] Benjamin Lammers, ‘The Birth of the East Ender: Neighborhood and Local Identity in Interwar East London’, Journal of Social History, Vol. 39, No. 2, (2005), pp. 331-344 (pp. 338-9)

[2] Martin Edwards, ‘Introduction’, in Leonard Gribble, The Arsenal Stadium Mystery, (London: British Library, 2018), p. 7

[3] Gribble, The Arsenal Stadium Mystery, p. 123

[4] Ibid., p. 119

[5] Ibid., p. 19

[6] Ibid., p. 38

[7] Ibid., p. 171

[8] Ibid., p. 106