As is tradition, the final blog post of the year looks back at New Year’s Eve one hundred years ago. You can read the 1921 edition here and the 1922 edition here.

In 1923, New Year’s Eve fell on a Monday. Unlike today, when British workers generally get given the 1 January off as a Bank Holiday, in the 1920s staff in London had to work as normal on the first day of the new year. ‘Northerners’ apparently did get the day off. The Evening Standard, as London’s evening paper, reported on 1 January:

London to-day is largely populated by tired but happy people who but a few hours ago in a thousand various ways were deliberately making a night of it. And none of them seem ashamed of it. Their eyelids may sag as they bend over their work, but they are full of conscious virtue. They have begun the New year well.[1]

As was common every year, the New Year’s Eve celebrations in the capital were reported to have been the most successful yet, although it appears to have been raining heavily on 31 December 1923. The people of London celebrated in the usual way: the rich went to hotels and restaurants, and everyone else partied on the streets, with St Paul’s cathedral a particular focal point for those who were perhaps religiously-minded. The Daily Telegraph noted that well-heeled Londoners increasingly stayed in a hotel for the whole Christmas period: ‘It is not at all unusual for groups of friends to move into an hotel for Christmas and the New Year, thus, while enjoying the nightly round of festivities, avoiding the trouble of getting home to the suburbs in the early hours of the morning.’[2] The ‘shortage of servants’ which was starting to bite in the post-War years, was quoted as one reason to outsource all Christmas festivities to professional caterers.

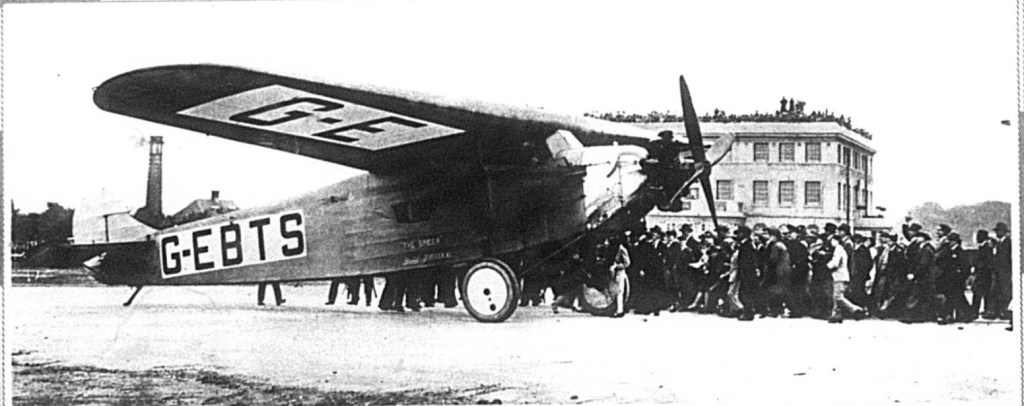

Although celebrations in London were largely business as usual, two things happened on New Year’s Eve 1923 that radically altered the nation’s experience of the festive period. The BBC had been founded in October 1922, and by the end of 1923 it had sufficiently established itself, and enough people in the country now owned wireless (radio) sets, to allow two things to happen. First, at 6.35pm, the Archbishop of Canterbury addressed the nation with a New Year’s message. As the Manchester Guardian reported: ‘every word came through quite clearly. The Archbishop spoke from the British Broadcasting Company’s premises in London.’ His speech related the ‘glamour’ of the War years to the ‘common-place’ lives most people now found themselves in:

We must translate the poetry and glamour of the exciting war years into the prose of common days. The Ypres salient, or the North Sea minesweeper on a stormy night, or the Anzac beach and cliff, or the midnight vigil of the hospital, with the ghastly stretchers coming in: these things, with all their dreadness, had an uplift of their own. There is no such uplift in your rather commonplace sitting-room, or at the clerk’s dull office desks, or behind the shop counter. But such are the “settings” in 1924 of many of the self-same men and women who six years ago had the other, the “romantic” setting.[3]

Although we may today primarily think of the 1920s as a decade of glitz and glamour, the Archbishop clearly picked up on a mood of discontent in the nation. Presenting the war as glamorous and exciting is a shift away from how newspapers had generally discussed the war until that point, as a period of hardship and sacrifice. The increased distance from the horrors of war allowed space for alternative viewpoints to be aired.

The other momentous thing that happened was that for the first time ever, the whole country could hear Big Ben chime at midnight over the radio:

Cover it up as we may, it is a solemn moment as the New Year is ushered in. And these sonorous notes of Big Ben, carried so magically through space, struck the right note at the right moment. (…) The broadcasting of Big Ben is a big idea which will remain with us. It has something of the power of the Two Minutes Silence in it.[4]

The Evening Standard reporter had the right instinct, as the chiming of Big Ben is still broadcast by the BBC and still the definitive start of the new year across the British isles. In 1924, it demonstrated the unifying power of the new mass media, binding together people from all across the country to the same moment and sound; and irrevocably placing a historical London landmark at the centre of that unification. How different would it be if instead, the BBC had chosen to broadcast church bells from Middlesborough, Swansea or Perth?

The New Year’s Honours list, normally good for extensive coverage in newspapers, got very short shrift in 1924. It was shorter than usual, there was no-one on the list who may be known by the wider public, and there were no women on it at all – the latter was, even in 1924, unusual.[5] There were also no interesting new laws that were coming into effect on 1 January 1924. Where’s 1923 had seen a change to the divorce and unemployment laws which potentially affected millions, in 1924 the most significant new law was the ‘Salmon and Freshwater Fisheries Act (…) designed to prevent the destruction of salmon and trout by such methods as the use of the spear and explosives.’[6]

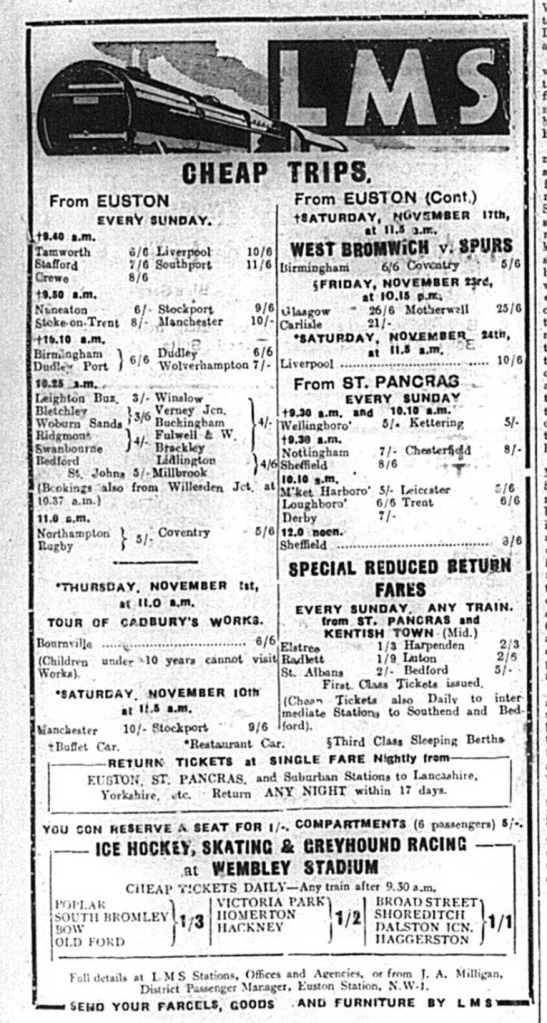

Finally, the London Underground shared its annual statistics with the readers of The Times. In 1923, it transported 1.7 billion passengers: ‘so that every Londoner travelled, on average, 219 times in the year in either its railway cars, tramcars or motor omnibuses.’[7] It was the busiest year yet for the transport body. The advert links this increase in travel to an increase in general employment figures: ‘The number of passengers is growing steadily. This means that trade is improving and unemployment lessening.’ For the new year, the board predicted continued expansion of both passenger numbers and rolling stock.

A general note of optimism pervaded the newspapers at the start of 1924, although the memories of the First World War were fading away. There were no references to relief that the war was over, or remembrance of those who had fallen. Instead, the Archbishop’s speech indicates that relief was being replaced with frustration and boredom. The country had to figure out how to settle back into normality after years of disruption that, with hindsight, could have taken on a sheen of glamour.

[1] ‘London goes to work on the “morning after”’, Evening Standard, 1 January 1924, front page

[2] ‘Greeting the New Year – Music, Mirth and Dancing’, Daily Telegraph, 1 January 1924, p. 7

[3] ‘Primate Broadcasts his New Year Message’, Daily Telegraph, 1 January 1924, p. 13

[4] ‘London goes to work on the “morning after”’, Evening Standard, 1 January 1924, front page

[5] ‘A Londoner’s Diary’, Evening Standard, 1 January 1924, p. 4

[6] ‘New Legislation’, The Times, 1 January 1924, p. 9

[7] ‘A New Year’s Message from the Underground’, The Times, 1 January 1924, p. 10