Although British literature of the interwar period is today perhaps popularly associated with the modernism of Virginia Woolf, during the 1920s and 1930s other, less experimental authors were equally, if not more, well-known. John Galsworthy was one of the authors despised by Woolf as an ‘Edwardian’. His best-known work remain the novels that form the Forsythe Saga, but he was also a prolific playwright and a number of his plays were adapted to film during the 1930s. Galsworthy was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1932, mere months before his death.

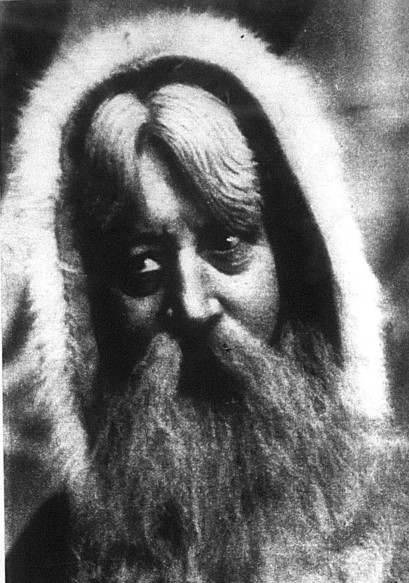

One of Galsworthy’s last plays was Escape, which was first performed in the West End in 1926. The play transferred to Broadway the following year, where the lead role was performed by Leslie Howard. In 1930, Galsworthy collaborated with director/producer Basil Dean in adapting the story for film for Associated Radio Pictures. The film version starred screen stalwart Gerald du Maurier in the lead role of Captain Matt Denant. The brief period between the play’s premiere and the film’s release, in addition to the high-profile actors attached to both productions, indicates Galsworthy’s fame and popularity during the interwar period.

The story of Escape is somewhat unusual compared to other mainstream interwar outputs. Whereas most cultural productions of the period seek to reinforce the importance of the state in maintaining an orderly society, Escape opens with a direct challenge to authority. Captain Matt Denant, a celebrated war hero, goes for a walk in Hyde Park in the evening. Hyde Park was known as a favourite spot for prostitutes. During the interwar period, the Home Office worked hard on the management of street prostitution in London.[1] Yet the Metropolitan Police’s hard line on soliciting meant they sometimes overstepped the mark, and police officers arrested women who had not been soliciting at all.[2]

Magistrate courts, frustrated with what they perceived to be an influx of cases with insufficient evidence, insisted that in future, it would be a requirement for the man who was being solicited to provide evidence against the accused woman – women would no longer be convicted on the basis of police evidence alone.[3] This complex legal debate is key to understanding the opening of Escape. Once Captain Denant walks through the park, a prostitute comes up to him and solicits. Denant good-naturedly turns down her offer and is about to continue on his way – however, a plain-clothes police inspector has witnessed the interaction. He approaches Denant and asks him to make a statement that the woman was soliciting. In light of the higher evidence bar set by the magistrate courts, this second statement would be a requirement for any conviction. Denant refuses to co-operate and the interaction with the police officer escalates to the point that Denant hits him. The police officer hits his head and dies; Denant gets arrested and convicted for manslaughter.

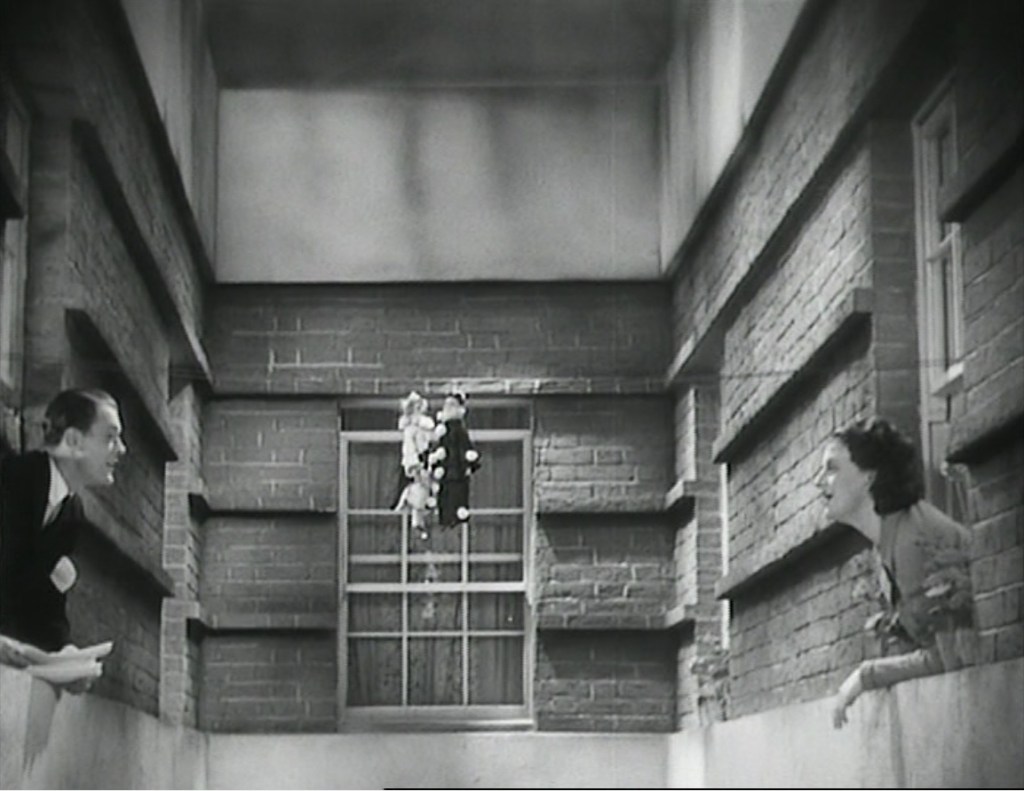

After this extraordinary opening, Denant is transferred to Dartmoor, one of the most notorious prisons in the country at this time. Rather than accepting his punishment, Denant manages to escape while on work detail, and the remainder of the play/film tracks him as he encounters various people who help him on his flight. Ultimately, a parson is willing to lie to the police, who are hot on Denant’s trail. This gives Denant a moral dilemma and he decides to give himself up to protect the parson.

Not only does Denant refuse to help the police officer in the opening scene to convict a prostitute, he then rejects the punishment he is given for the manslaughter of the officer. Arguably, the prison sentence meted out to him is fair and appropriate, yet Denant does not initially accept it. This indicates he, to a certain extent, places himself above the law. He only ultimately agrees to undertake his prison sentence because he does not want to morally compromise a previously uninvolved third party – not because he necessarily thinks it is appropriate for him to be imprisoned for his actions.

Although Galsworthy was considered an ‘establishment’ writer, the protagonist in Escape rejects the conventional structures of state authority and is willing to go to considerable lengths to avoid any involvement with them. In the opening scene, Denant does not display any of the moral outrage or shock commonly associated with streetwalking in the popular media of the time. Throughout the action, he retains a keen sense of independence and trust in his own judgement: even when he does ultimately agree to sit out his prison sentence, he does so on his own terms.

This is in stark contrast to the majority of plays and films of the interwar period, in which the police in particular are presented as the unchallenged face of authority, which must be obeyed to avoid a breakdown of social norms. In Escape, Galsworthy ostensibly offers up an alternative point of view in which independent judgement rules supreme, even if that does not align with the rule of law. However, Denant’s ultimate acquiescence to the prison sentence, whether arrived at from a sense of moral obligation or not, ensures that in the end of the story social order is restored.

[1] Stefan Slater, ‘Containment: Managing Street Prostitution in London, 1918-1959’, Journal of British Studies, Vol. 49, no. 2 (2010), 332-357

[2] Julia Laite, ‘The Association for Moral and Social Hygiene: abolitionism and prostitution law in Britain (1915–1959)’, Women’s History Review, Vol. 17 (2008), 207-223

[3] Stefan Slater, ‘Lady Astor and the Ladies of the Night: The Home Office, the Metropolitan Police and the Politics of the Street Offences Committee, 1927-28’, Law and History Review, Vol. 30, no. 2 (2012), 533-573