As is tradition on this blog, for the final post of the year we cast our minds back to exactly one hundred years ago and have a look at how New Year’s Eve was celebrated in London that night. After some rain earlier in the day, the evening of Sunday 31 December was cold and a bit windy but dry: no doubt a relief to Londoners keen to let their hair down.[1] According to the Manchester Guardian pre-midnight celebrations were ‘more subdued’ than in previous years owing to 31 December being a Sunday! Due to a special licensing hour dispensation, hotels could stay open till 2am.[2]

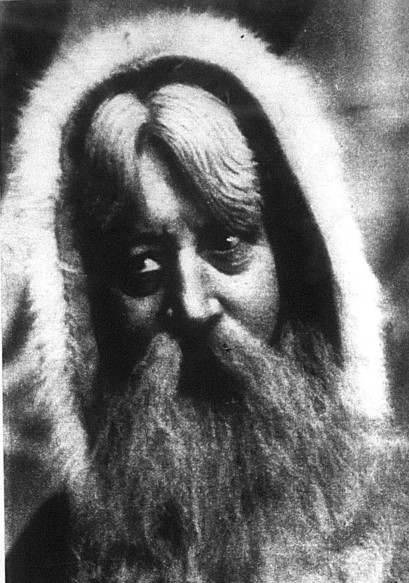

Well-heeled Londoners were excited to ring in the new year with elaborate parties in hotels and restaurants. Hotels spared no cost in their interior decoration: the dining room of the Berkeley Hotel ‘was transformed into a lighted vineyard’ and at Claridge’s guests walked through an Italy-inspired landscape.[3] At the Savoy Hotel, a large amount of Christmas crackers were pulled during an ‘elaborate banquet’ – 25,000 crackers according to the Daily Express, but 35,000 according to the Mirror.[4] Some venues put on performances: at the Metropole Hotel midnight was marked by ‘a dainty little girl dressed as Cupid [appearing] from a huge cracker, which was pulled by Father Christmas.’[5] At the Piccadilly Hotel grill room a female singer appeared out of the top of a huge champagne bottle at midnight to sign Auld Lang Syne.[6]

For those who could not afford to be in the hotels, the streets of London provided a suitable party venue. The steps of St Paul’s Cathedral were one of the traditional sites of celebration, and crowds started gathering there hours in advance.[7] The Daily Express reporters, always ready with more evocative language then their colleagues at rival papers, described the crowds in the West End as follows:

They were “grown ups” who surged in dense masses through the streets, but the joy of childhood – Christmas party childhood – was rampant. Every one wore a paper hat, and nearly every one was blowing a toy trumpet. Street corners were impromptu ballrooms.[8]

Aside from the evening celebrations, the New Year also meant the publication of the annual honours list, announcing which luminaries had been bestowed honorary titles. In 1923, the prominent and popular Home Office pathologist, Bernard Spilsbury, was knighted and could henceforth call himself Sir Bernard Spilsbury.[9]

The beginning of the new year also meant the start of winter sales in all the big department stores. The growing importance of consumerism, and the increase in disposable income, are marked by the prominent articles appearing in the popular press about the sales. ‘Thousands of women will to-day celebrate the coming of 1923 by “raiding” the great London stores in the breathless but happy hunt for bargains’ predicted the Daily Mirror.[10] In an article that essentially sums up the offers at each of the great stores, readers are advised that whilst buying ‘indiscriminately’ is never a good idea, one can’t go wrong with staples such as ‘gloves, shoes, underclothes etc’.[11]

The Sunday papers on 31 December had already carried large adverts for each of the store, preparing shoppers to the bargains that could be had. Like the Daily Mirror article, these were almost exclusively aimed at the female readership. It was clearly understood that shopping in a sale was the kind of frivolous activity that only women would engage in. At Dickins & Jones, a clearance of ‘model gowns’ (ie. those used for display purposes) meant that prices started at 7 ½ guineas – a guinea being 1 pound and 1 shilling.[12] On the same page, competitor Marshall & Snelgrove advertised a fur coat for 89 guineas; it had previously been between 125 and 179 guineas so this discount was indeed a ‘wonderful bargain’ although it was clearly out of reach for the vast majority of the population.[13]

By the time the Evening Standard appeared in the afternoon, it was able to report on the ‘bargain day scenes’ in breathless and rather sexist tones. ‘The occasion had much more significance for the ladies than the mere advent of the New Year, and (…) they stormed the whole of the shopping centres in their myriads.’[14] Some of the items on offer according to this article were velour coats with mole collar and cuff trimmings at 4 ½ guineas, and a knitted woollen gown at 27 shillings and sixpence; clearly the readership of the Evening Standard had less to spend than the readers of the Observer.

Elsewhere, the Evening Standard reported on the continued imprisonment of Edith Thompson and Freddie Bywaters, who would be executed on 9 January for the murder of Edith’s husband. Other papers noted the republic of Ireland’s recent independence, which was officially finalised in December 1922.[15] All was not well in the remainder of the Union either, with Scottish hunger marchers protesting in London on the first day of 1923.[16] Although the New Year’s Eve parties and January sales gathered the most prominent coverage, it is clear that below the celebratory surface troubles were brewing as Britain continued to deal with the fall-out of the Great War.

[1] ‘Week-end Weather’, The Observer, 31 December 1922, p. 14

[2] ‘New Year Revels in London’, Manchester Guardian, 1 January 1923, p. 7

[3] ‘At the Hotels’, Daily Express, 1 January 1923, front page

[4] Ibid.; ‘1923 Danced In by Merry Throngs’, Daily Mirror, 1 January 1923, p. 3

[5] ‘1923 Danced In’, Daily Mirror

[6] ‘New Year Revels in London’, Manchester Guardian

[7] Ibid.

[8] ‘Great Crowds in the Streets’, Daily Express, 1 January 1923, front page

[9] ‘New Years Honours’, Daily Express, 1 January 1923, p. 7

[10] ‘Sales Carnival Begins To-Day’, Daily Mirror, 1 January 1923, p. 2

[11] Ibid.

[12] ‘Dickins & Jones’ advert, The Observer, 31 December 1922, p. 9

[13] ‘Marshall & Snelgrove’ advert, The Observer, 31 December 1922, p. 9

[14] ‘Bargain Day Scenes,’ Evening Standard, 1 January 1923, front page

[15] ‘Politics at Home and Abroad’, Daily Telegraph, 1 January 1923, p. 4

[16] ‘Hunger Marchers’ Complaints’, Evening Standard, 1 January 1923, p. 8