As has been covered on this blog before, in 1927 the British Government adopted the Cinematograph Films Act, a legal measure which prescribed a minimum volume of British-made films which each exhibitor had to show. It was no longer possible for a cinema to solely show Hollywood films. The intention of the Act was to boost the British film industry; its unintended consequence was that American studios set up cheap studio contracts in Britain and started churning out low-quality films which became known as ‘quota quickies’.[1]

Shortly after the Act was passed, Britain started transitioning to sound film, with the earliest ‘talkies’ with continuous sound appearing in 1929/1930. The transition was rapid, with sound film becoming the norm within just a few years. Yet for the ‘quota quickie’ industry, sound film could be an expensive business. It was generally the aim of American studios to shoot their British films as cheaply as possible, often for as little as £1 per foot of film.[2] Shooting sound film required additional technology such as microphones, and also forced on-set shooting in the early years, as location shooting was too noisy and complicated. It is not surprising, then, that quota quickie producers continued to make silent films into the early 1930s.

One of these is The Woman from China, which was made in 1930. According to Steve Chibnall, the film was produced in a rush. Under the 1927 Act, the ‘quota year’ ran from 1 April to 31 March, meaning that by 31 March each year exhibitors had to be able to evidence that they had shown the appropriate proportion of British films in the preceding twelve months. In January 1930, the major American studio MGM commissioned two British producers to create a film by the end of March that year. The result was The Woman from China, for which shooting and editing was completed within four weeks, with a half-finished script.

The final scenes were shot five days before the scheduled trade show, and director Dryhurst was obliged to double as editor with the help of one young assistant. The two worked ninety hours without sleep to meet the deadline, although the first of the two shows as lacking the final reel.[3]

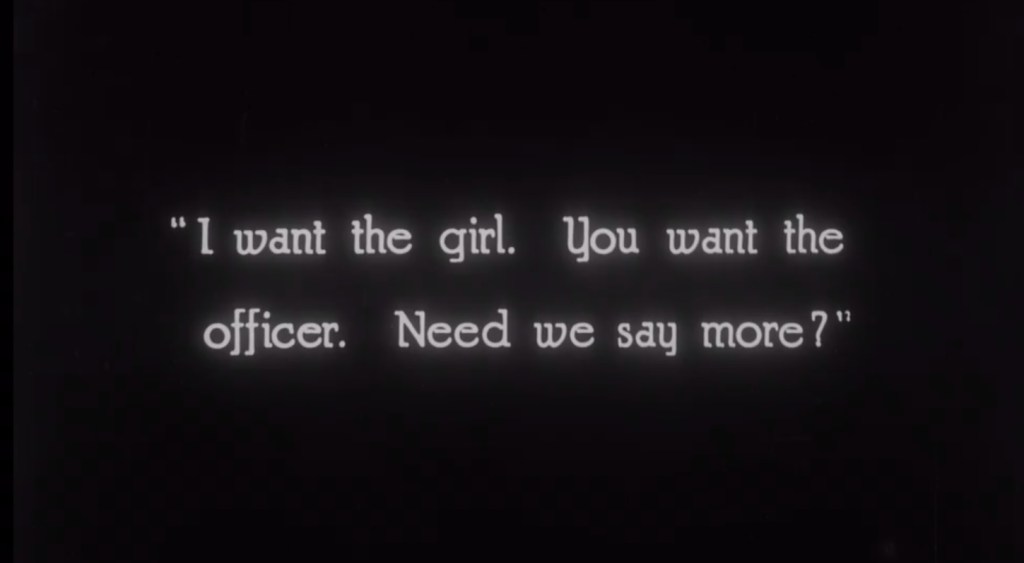

Considering those circumstances, The Woman from China can be considered a fairly accomplished film from a technical perspective, although it perpetuates many obvious and damaging stereotypes in its narrative, staging and costuming. The plot is one familiar from films of this period: a young secretary and a naval officer are engaged, but their relationship is thwarted by a mysterious British woman who has recently arrived from China, and who is in love with the naval officer. The ‘woman from China’ is being blackmailed by a Chinese Svengali, Chung-Li, who in turn wants to marry the secretary. The Chinese man directs his henchmen to kidnap both the officer and the secretary, and proceeds to emotionally torture them until they can break free. The ‘woman from China’ has a change of heart and sacrifices herself to save the naval officer; the Chinese man and his henchmen are killed; and the original couple are able to get away unscathed.

There was already an established history of racist depictions of Chinese characters in popular culture in Britain. The most successful proponent of this was pulp writer Sax Rohmer, who started his ‘Fu Manchu’ series of books just before the First World War. In these books, a Chinese evil mastermind is working to reinstate China as a superior power. Fu Manchu is associated with Limehouse, which at that time was London’s Chinatown. The Woman from China acknowledges its debt to these earlier pulp novels by a character noting that Laloe Berchmans, the woman who has made a deal with Chung-Li, is ‘like a character from an Edgar Wallace novel.’

Chung-Li is played by white British actor Gibb McLaughlin in yellowface. The second most prominent Chinese character, an anonymous ‘Chinaman’, is played by Japanese actor Kiyoshi Takase. The Woman from China incorporates such racist tropes as Chung-Li having pointedly filed fingernails; leering after the secretary; and working to increase China’s power in the world. (I’ve deliberately not included any stills from the film featuring McLaughlin in this post as his costume and appearance throughout is offensive).

Although The Woman from China may appear to be a good example of a 1930s British film that is best forgotten about, it also allows us to explore the conditions of film production during this volatile period of the British film industry; contemporary portrayals of race; and a late example of a British silent film which includes on-location shooting. Its preservation allows us to appreciate the full range of British film output of this period, and to engage with the challenging legacy of racial discrimination which was pervasive in Britain during the interwar years.

Readers based in the UK can watch The Woman from China for free on the BFI Player.

[1] Steve Chibnall, Quota Quickies: The Birth of the British ‘B’ Film (London: BFI, 2007), p. 4

[2] Ibid., p. xii

[3] Ibid., p. 19