Dorothy L. Sayers is readily regarded as one of the most prominent contributors to the ‘Golden Age of Crime Fiction’: a period that spans nearly all of the interwar period. It marked not only a huge increase in the popularity of crime stories in Britain, but also saw innovations in the genre, for example the unreliable narrator in Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926) and a crime with half a dozen possible solutions in Anthony Berkeley’s The Poisoned Chocolates Case (1929).

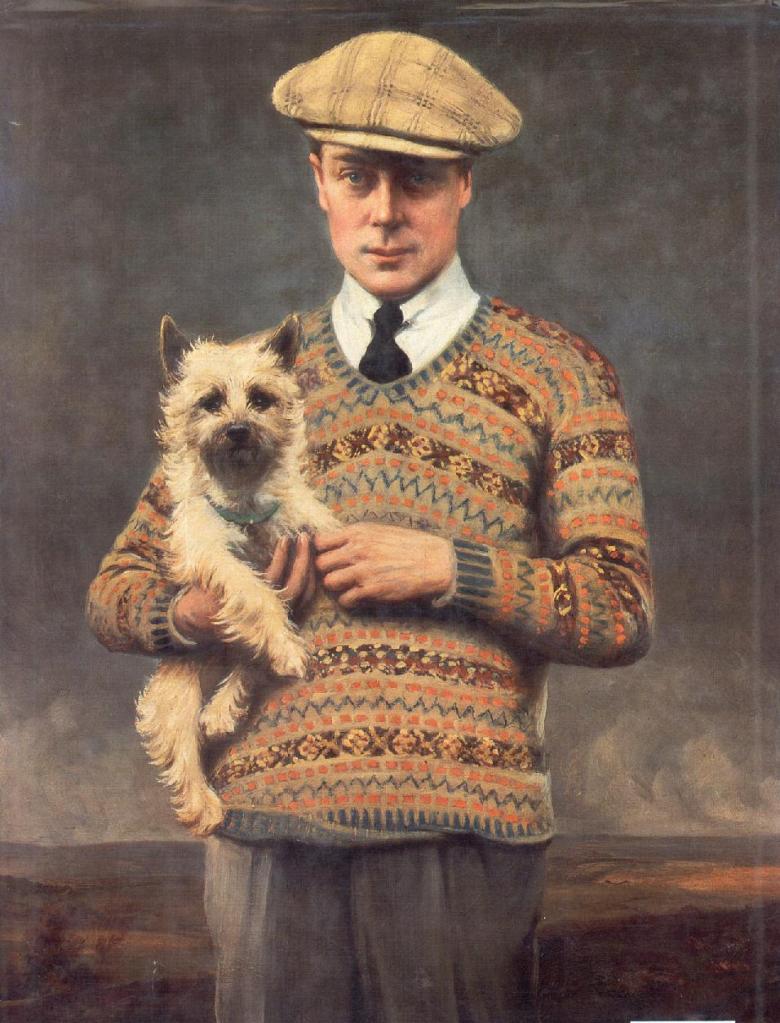

Sayers’ main contribution to the genre were the eleven novels she wrote around amateur sleuth Lord Peter Wimsey; the debonair younger brother of the Duke of Denver who combines a passion for antiquarian book-collecting with his hobby of crime detection. The first Wimsey novel, Whose Body? appeared in 1922 in the US and in Britain a year later. Sayers’ continued writing Wimsey novels until Busman’s Honeymoon in 1937, after which she turned her attention to writing scholarly works on theology.[1]

The eight Wimsey novel out of a total of eleven, Murder Must Advertise, appeared in 1933. In this book, Wimsey goes undercover to work as a copywriter at a fictional advertising firm, Pym’s Publicity. He is invited to do this by the manager, Mr Pym himself, after a suspicious death on the firm’s premises: one of the staffers has fallen to his death from a spiral staircase. Sayers drew on inspiration from her own time working as a copywriter in the early 1920s for S.H. Benson; the Benson office even had a steep spiral staircase like the one that appears in Murder Must Advertise.[2]

Sayers’ real-life work experience lend the novel’s descriptions of the office life in an advertising firm an authentic air. The novel’s opening sees all the firm’s office staff gathered in the typists’ room, to surreptitiously organise a sweep on the horse races. There are pages of rapid, overlapping dialogue of staff discussing the sweep and the arrival of the new colleague. When they hear one of the managers approach,

‘the scene dislimned as by magic. (…) Mr Willis (…) picked a paper out at random and frowned furiously at it (…) Mr Garrett, unable to get rid of his coffee-cup, smiled vaguely and tried to look as though he had picked it up by accident and didn’t know it was there (…) Miss Rossiter, clutching Mr Armstrong’s carbons in her hand, was able to look businesslike, and did so.’[3]

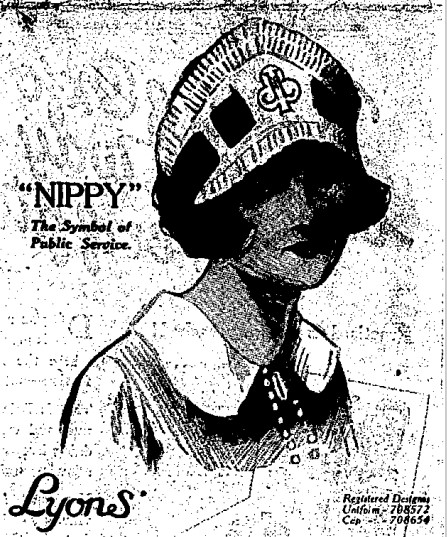

It is a scene still familiar from modern office-based comedies and dramas such as Mad Men (2007-2015) and The Devil Wears Prada (2006). Throughout the book, the copywriting staff spend most of their time chatting and trying to come up with new slogans, interspersed with bursts of extreme stress when an advert needs to be reworked close to the printing deadline. A key scene in the novel sees the Morning Star newspaper ring the office at 6.15pm because they have noticed an unintentionally rude image in one of the adverts due to be printed that evening.[4] The resolution to the murder investigation ultimately also lies in the adverts: Wimsey finds out that a drug racket uses advertisements to communicate with one another.

Because of Wimsey’s aristocratic background, he does not normally engage in paid work in any of the books. Alongside the murder mystery, Murder Must Advertise gives the reader the opportunity to glimpse the world of advertising in 1930s Britain. The subject matter gives Sayers’ ample opportunity to poke fun at the public. During his time at Pym’s, Wimsey accidentally comes up with a wildly successful campaign for (fictional) Whifflet cigarettes:

‘It was in that moment, (…) that [Wimsey] conceived that magnificent idea that everybody remembers and talks about today – the scheme that achieved renown as ‘Whiffling Round Britain’ (…) It is not necessary to go into details. You have probably Whiffled yourself.’[5]

Essentially, the campaign is a coupon scheme; coupons collected on cigarette packets could be traded for hotel stays, train tickets, holiday outings et cetera. Sayers’ describes the scheme as growing beyond the initial campaign to

‘Whifflet wedding[s] with Whifflet cake[s] (…) a Whifflet house, whose Wihfflet furniture included a handsome presentation smoking cabinet, free from advertising matter and crammed with unnecessary gadgets. After this, it was only a step to a Whifflet Baby.’[6]

At the time the novel was published, this type of all-encompassing branding had also been embraced by the British Union of Fascists, as discussed in a previous post. Advertising and marketing in general had taken an enormous flight during these decades, in no small part due to the increased circulation of daily newspapers.

Sayers herself is sceptical of the industry – the novel ends with a paragraph of fictional advertising slogans and the closing line ‘Advertise, or go under.’[7] Although Sayers apparently enjoyed her time working at S. H. Benson in 1923,[8] when Murder Must Advertise was published ten years later she appears to have been more critical of the industry. Nonetheless, Murder Must Advertise provides a comic look into what was a growing industry in interwar Britain, written by someone with first-hand knowledge of its operations.

A 1973 TV adaptation of Murder Must Advertise can be found on YouTube.

[1] Francesca Wade, Square Haunting: Five Women, Freedom and London Between the Wars (London: Faber & Faber, 2020), pp. 329-331

[2] Martin Edwards, The Golden Age of Murder (London: Collins Crime Club, 2016), p. 13

[3] Dorothy L. Sayers, Murder Must Advertise (London: New English Library, 2003 [1933]), p. 6

[4] Ibid., pp. 135-145

[5] Ibid., p. 288

[6] Ibid., p. 289

[7] Ibid., p. 388

[8] Wade, Square Haunting, p. 125