This is the eleventh and final part in the investigation into the 1934 ‘Bow Cinema Murder’. You can read all entries in the series here.

After John Stockwell’s execution on 14 November 1934, the Bow Cinema murder case had formally come to a close – but its impact on the people caught up in it lasted beyond the execution. Most significantly, Maisie Hoard continued to recuperate from the substantial injuries that Stockwell had inflicted on her. The psychological damage was naturally also serious. On the day of the execution an interview with Maisie appeared on the front page of the Daily Mirror, under the headline ‘Life Ruined by Murder’. Still in hospital at this stage, Maisie revealed that she would have a scar in her face for the rest of her life. She also pointed out that, as a new cinema manager had been appointed to the Eastern Palace Cinema, she was now effectively homeless:

I have now no home – nothing. I have nowhere to go, for I have no mother, brother or sister. My husband was uninsured – so I have no money. I do not ask for charity. All I want is work. Will someone give me a job as housekeeper?[1]

In the end, Maisie did not have to work as a housekeeper, or at least not for long. By 1939 she had remarried to a Henry White and moved to Ashford in Kent.

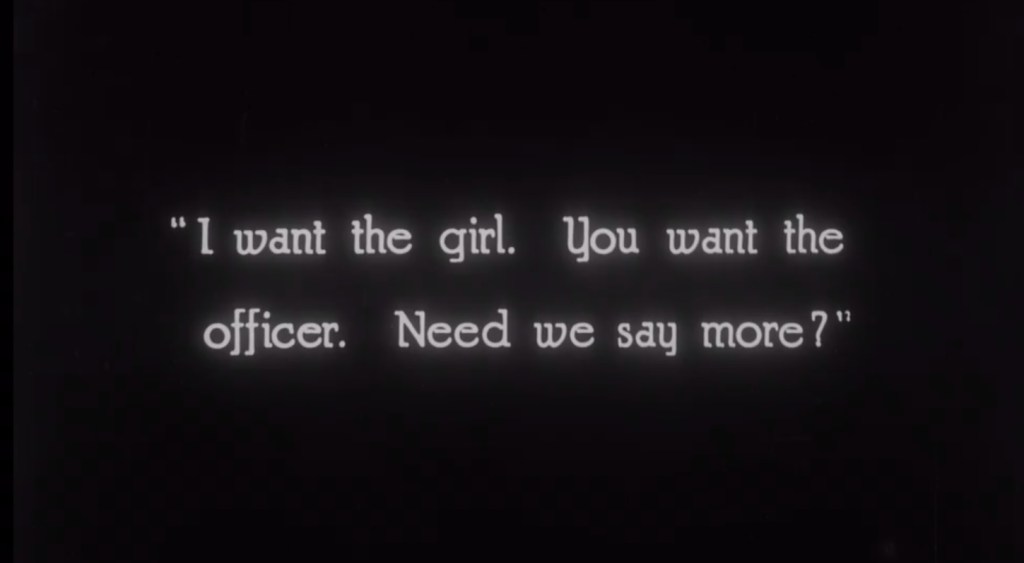

The other woman whose life had been most affected by John Stockwell was his girlfriend, Violet Roake. As noted in the previous instalment of this series, she had also gone public and was interviewed in the Daily Herald, reframing her story as a romance novel. Violet was only 18 in 1934 and although she had anticipated marrying John Stockwell before he committed his crime, she clearly had enough opportunity to find another life partner. It is possible that her reputation in the East End was irrevocably tainted though; while her brother and sister stay local, Violet marries a Navy officer and moves to Portsmouth. The couple married in 1939 and had a son in the same year, and a daughter ten years later. Violet lived until 1991. Her husband, Joseph Brimley, survived her and lived until 1995.

For Fred ‘Nutty’ Sharpe, the Chief Inspector who investigated the case, the Bow Cinema murder investigation was significant enough to warrant a full chapter in the memoirs he published in 1938. Sharpe retired from the CID in 1937. In his book, Sharpe of the Flying Squad, he calls Stockwell ‘the calmest, most coldblooded individual I have ever met and he wasn’t the least bit nervous.’[2] Throughout the chapter Sharpe uses superlatives to stress the violence of the murder: it was ‘one of the most savage [murders] a man has ever committed’ and the attack had been committed with ‘utmost violence.’[3] He juxtaposes this with his descriptions of Stockwell as’ completely unmoved and in entire possession of his nerve.’[4]

Sharpe’s descriptions reinforce the newspaper reporting that had taken place during the case, which also largely described Stockwell as calm and weirdly devoid of emotion. Despite this, though, John Stockwell never entered the popular imagination as a notorious calculating killer. There are plenty of well-known murder cases from the interwar period, but this is not one of them. For a case that was considered at the time to be extremely brutal, and a killer who was unusually young and unemotional, it may seem surprising that this case did not gain the same notoriety as others.

It is not because this case was satisfactorily solved – most of the best-known interwar murders were resolved at the time and their convictions are largely considered sound. Like many of the other famous cases, celebrity pathologist Sir Bernard Spilsbury worked on this case, and it received extensive press reporting. It raised concerns about the callousness of youth, and whether it was appropriate to execute a 19-year old.

I suspect that it is the combination of victim and killer that has made this murder less appealing than others of the same period. Unlike many of the most famous interwar murders, there was no love or domestic angle to this case. There were no betrayed husbands or deserting wives; Stockwell hadn’t murdered a girlfriend like Patrick Mahon or Norman Thorne, or tried to fake his own death due to having too many girlfriends, like Alfred Rouse. He also had not been convicted of killing his own mother, like Sidney Fox. Instead, he was a man killing another, unrelated man, for financial gain. Most years during the interwar period, a handful of men got executed for similar crimes, yet the cases are largely forgotten. Instead, the interwar years are remembered for their colourful domestic dramas, with cases like Edith Thompson’s being so well-known she has a dedicated website.

As this series has demonstrated, the killing of a man by another man can be no less interesting than a murder case involving a jilted lover; and it can reveal much about the attitudes towards masculinity, class, money, and local communities.

[1] ‘Life Ruined by Murderer’, Daily Mirror, 14 November 1934, front page

[2] Frederick Sharpe, Sharpe of the Flying Squad (London: John Long, 1938), p. 126

[3] Ibid., pp. 126-7

[4] Ibid., p. 131