As the UK getting used to a new monarch on the throne, let’s cast our minds back to the events of 1936, when an abdication crisis ultimately resulted in the confirmation of Prince Albert, the second son of King George V, as King George VI.

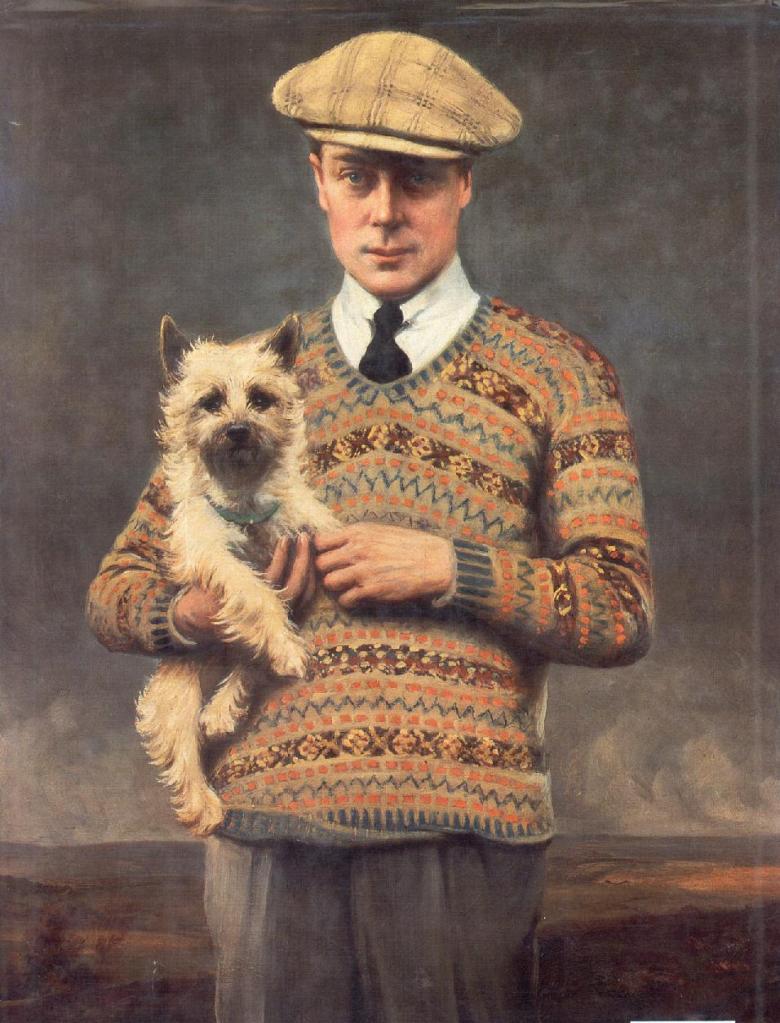

Prior to 1936, and throughout the 1920s, George V’s eldest son Edward, Prince of Wales, was an enormously popular figure. This blog has previously touched on his popularity as a newsreel subject and his ability to kick off new fashion trends. Edward was often seen in London’s nightlife and also travelled a great deal, both for work and for pleasure. He had the reputation of a playboy and remained unmarried in 1936, when he was already 42 years of age. His brother George, by contrast, was a year younger than him but had married at 28 and fathered two children (Elizabeth and Margaret) by the time he was 35.

As is customary in Britain, George V reigned until his death and the eldest child [at the time, the eldest son] is declared monarch immediately afterwards. A formal coronation ceremony follows some months later. When George V passed away in January 1936 after a long period of declining ill-health, Edward was duly proclaimed King. The abdication crisis ensued when, in the autumn of 1936, Edward declared his intention to marry the American divorcée Wallis Simpson.

Wallis’ nationality was already something that spoke against her in a country that was, at the time, concerned and suspicious of American cultural influences through popular culture. The popularity of Hollywood films and dance bands was blamed for a host of cultural ills. But Wallis’ past relationships were the real obstacle to the match. Edward had first met her as early as 1931 and she did not file for a divorce from Mr Simpson until October 1936, making it abundantly clear that her relationship with Edward had started during her marriage.

Although one of the key reasons that the Church of England was created was famously to allow Henry VIII to divorce Catherine of Aragon, divorce was a significant social taboo in interwar Britain. Divorce laws were eased in the 1920s but the social stigma on divorce was still significant – and not helped by the gleeful reporting of high-profile divorce cases in a tabloid press keen to increase its readership. The key objection which Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin therefore proposed against Edward’s marriage to Wallis was that ‘the people’ would not accept her as Queen. After several months of legal tussle between Edward and the government, it became clear that a marriage between Edward and Wallis would not be accepted as long as he was on the throne. In December 1936, Edward formally abdicated and his brother Albert was proclaimed King, styling himself as George VI. Edward was never officially coronated; his coronation had been planned for May 1937; a date eventually used for the coronation of George VI instead.

One of the aspects of the abdication crisis that is difficult for a modern audience to comprehend is how absolutely the British newspapers refused to print anything about it until early December 1936. As this blog has frequently noted, newspapers were extremely popular and influential during the interwar period, and in the mid-1930s popular newspapers in particular were constantly trying to increase their circulation figures. A royal scandal of this magnitude would appear to be excellent content to draw in readers. However, the respect for the monarchy was such that newspaper proprietors, who were fully aware of Edward’s relationship with Wallis, agreed a media blackout.

Such a thing would of course be completely impossible in our current digital media landscape, but even back in 1936 London newsvendors sold international publications, and journalists in other countries had no scruples about reporting the story. American outlets in particular splashed on the story, which from their perspective could be told as a fairy tale of an American commoner falling in love with the (future) King of Britain. The overwhelming power of the British press, however, ensured that its refusal to print the details for months meant that the majority of the British public remained equally unaware. The media blackout during the crisis exemplifies the power of newspaper proprietors during the interwar period, and the very close relationships between the newspapers and the corridors of power – although it must be pointed out that this blackout was voluntary and press-driven, and not imposed by the government or the Royal household.

Shortly after Edward’s abdication, Britain was introduced to Mass Observation, an (eventually) influential research organisation which aimed to understand modern society by asking ‘normal’ people to share their observations on everyday life and historical events.1 After its founding in January 1937, its first published work included a collection of ordinary peoples’ views on the Abdication Crisis. Mass Observation in a way seems to react against the media blackout initially surrounding the abdication. While powerful newspaper proprietors decided to withhold the news from the public, Mass Observation gave the public at large an opportunity to respond to the crisis and give their opinions on it.

The abdication crisis was a pivotal cultural moment in interwar Britain, one that laid bare some of the machinations of the powerful news media and its close links with those in power; but which also facilitated the emergence of a more democratic way of understanding everyday culture. Although Edward’s decision to choose marriage over a royal appointment was a personal one, it had significant social ramifications.

- Frank Mort, ‘Love in a Cold Climate: Letters, Public Opinion and Monarchy in the 1936 Abdication Crisis’, Twentieth Century British History, Vol. 25, no. 1 (2014), p. 32