This is the tenth part in the investigation into the 1934 ‘Bow Cinema Murder’. You can read all entries in the series here.

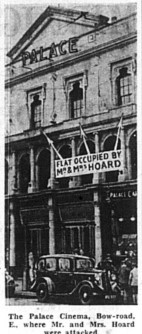

On 14 November 1934, just over three months after an intruder had repeatedly hit Dudley Hoard over the head with a hatchet to access the safe of the Eastern Palace Cinema, which he managed, John Frederick Stockwell was executed for the murder in Pentonville Prison. Because John had pled guilty to the charges, the death sentence was automatically passed under the provisions of the Capital Punishment Amendment Act 1868.

This Act set out that executions had to take place within prison walls; until 1868 executions in Britain had been public events. It also described the administrative provisions around the execution, proscribing the presence of ‘The Sheriff charged with the Execution, and the Gaoler, Chaplain, and Surgeon of the Prison, and such other Officers of the Prison as the Sheriff requires’. Although not explicitly spelt out in the Act, the method of execution was hanging.

The archival documents relating to the execution of John Stockwell show the extent to which capital punishment was part of the administrative business of state. Although there were relatively few executions in Britain during the interwar period (never more than 21 in a year, and some years as few as 3 across the whole country), the process was supported by proformas and other formal documentation.

On the day of Stockwell’s trial, the Governor of HMP Pentonville put in a formal request to the Prison Commission for a list of available executioners and records of their “conduct and efficiency”.[1] Two days later, on 24 October, the High Sheriff of the County of London formally fixed the time and date of the execution as 9am on 14 November (subject to appeal). On 12 November the Home Office formally notified the Prison Commission that Stockwell’s appeal was not upheld.

The day before the execution, Violet Roake visited her former boyfriend in prison one last time. She sold her story to the Daily Herald, who gave her a front-page article on 14 November in which she related her goodbye to John. The article claimed that Stockwell had been quite calm on the eve of his arrest, and had explained that he had committed the violent attack because he wanted to offer Violet a better life and future. The article further claimed that Stockwell accepted the consequences of his actions. The tone of the article was romantic, bordering on soppy. Violet was quoted as saying that Stockwell had looked ‘so well and handsome’ and that the prison wardens were ‘taking him away from [her]’.[2]

The article caused a stir in HMP Pentonville, and caused the Governor to write to the prison office and dispute some of the assertions made in the article, particularly around allegations made by Violet that she had struggled to get approval to visit John. Of course, by the time most people read the article, the execution had already taken place; it was an attempt to capitalise on the ‘human interest’ of what was framed as a tragic love story, not any serious protest against Stockwell’s execution.

The executioner was Mr R Barter of 25 Wellington Road, Hertfordshire. His assistant was Mr R Wilson of 15 Barnard Road, Manchester. Executions were always conducted by two men; due to the low numbers of executions each year, executioners usually had day-jobs and were called up as appropriate. As part of the proceedings, the Governor confirmed that the executioners were ‘respectable and of appropriate demeanour’; would not ‘lecture, interview or otherwise discuss the execution and thus discredit their office; and would not ‘create a public scandal through their (mis)performance of the execution.’[3] Just over ten years’ prior, the execution of Edith Thompson was rumoured to have gone badly wrong; clearly the Home Office were keen to avoid any scandals. The executioners’ responsibility to keep all details of the execution to themselves further worked to create an aura of mystery around capital punishment.

In the formal Notice of Execution completed the day after the execution, it was noted that John Stockwell had died of a broken neck, specifically because of a fracture between his 5th and 6th vertebrae. It was much preferred that prisoners died of a broken neck rather than of asphyxiation – the latter took longer and would be more uncomfortable for the prisoner. The British government prided itself on what it considered to be a most efficient and therefore superior system of capital punishment.

In line with the provisions made in the Capital Punishment Amendments Act, an autopsy was conducted on Stockwell’s body; this was undertaken by Bernard Spilsbury, who had also co-operated in the autopsy on Dudley Hoard’s body. Stockwell was then buried in the grounds of Pentonville Prison. At Scotland Yard, Detective Inspector Frederick Sharpe made his final report on the case, putting forward nine of the officers who had worked with him for rewards. All officers involved in the case received a commendation. Frederick Sharpe retired from the police in July 1937.

[1] PCOM 9/333 ‘STOCKWELL, John Frederick: convicted at Central Criminal Court (CCC) on 22 October 1934’, National Archives

[2] ‘Smile Recalled Many Times We Kissed’, Daily Herald, 14 November 1934, p. 2

[3] PCOM 9/333