Lancashire singer and comedian George Formby was an extremely popular entertainer during the interwar period. He had an instantly recognisable brand: catch-phrases such as ‘Turned out nice again!’; songs full of gentle innuendo and always accompanying himself with his banjolele (a cross between a ukulele and a banjo).

Supported by his wife Beryl as his manager, Formby made a series of comedy films in the second half of the 1930s, at the rate of two a year. These were often directed by Anthony Kimmins, a writer and director who also worked with that other Lancashire star, Gracie Fields. Kimmins and Formby’s sixth collaboration was Trouble Brewing, which was released in July 1939 and could serve as an antidote to the ever-increasing concerns about impending war in Europe.

In Trouble Brewing, Formby plays George Gullip, a newspaper printer at a fictional daily tabloid. George wants to be a detective, and has developed a type of ink which is impossible to rub off, to help him take fingerprints. The police are on the track of a gang which is distributing counterfeit money. When George and his friend Bill are duped by the gang, they team up with secretary Mary to unmask the gang once and for all.

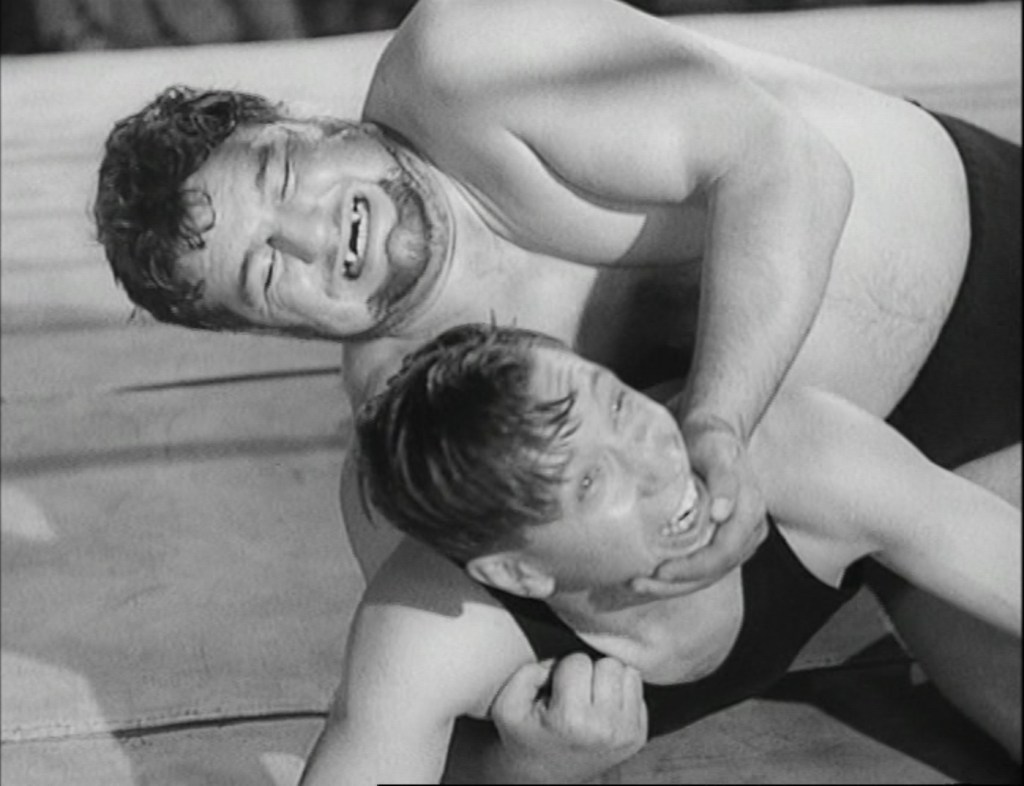

The film takes its title from the beer brewery which the counterfeiting gang uses as a front for their operations. As is common for these 1930s comedies that are primarily showcases for individual stars, Trouble Brewing consists of a series of set pieces which are only loosely strung together by a plot. George and Bill get duped on the racetrack; their subsequent investigations have them dress up as waiters at a private party; join a wrestling match; break into the police inspector’s home (and accidentally kidnap him); and confront the criminal gang in their brewery. At each stage, the script allows Formby plenty of physical comedy. His scenes with Mary and other female characters are opportunities for George to serenade them with his songs, even if they are more cheeky than romantic.

In Trouble Brewing, the line between journalism and policing is blurred to the point that it almost disappears. When George says to his superiors as the paper that he wants to become a detective, the newspaper proprietor harrumphs that being a journalist is pretty much the same thing. Although in reality, printers and journalists had very distinct professional identities, George moves between the basement print room and the editorial offices with relative ease. Mary, who works as the secretary to the newspaper’s editor, appears to know George and Bill and treats them as her direct colleagues.

The police in Trouble Brewing have been ineffective in rounding up the counterfeiting gang, which has been at work for at least six months at the beginning of the film. Yet the two printers and the secretary manage to close the gang down in a matter of days. There are plenty of other British interwar films in which journalists collaborate closely with the police, but Trouble Brewing takes this a step further by focusing on main characters who are not even actual journalists. At the same time it is tacitly assumed that George wants to get promoted and work as a journalist, which he achieves at the end of the film when both the newspaper proprietor and the police inspector are duly impressed with his work in rounding up the criminal gang.

Trouble Brewing gives Formby plenty of opportunity to exploit the sexual innuendo he was known for, not only in his songs but also in the scene when he and Bill serve as waiters at a private house party. The party is thrown by an opera singer, whom George and Bill suspect may be part of the criminal gang. George has gotten the singer to put her fingerprint on a piece of paper, but she put that piece of paper in the top of her stocking. When the woman sits down to speak to a male guest at her party, George creeps under the table in an attempt to get the paper. The woman naturally assumes that her conversation partner is touching her leg under the table. This joke is repeated three separate times, causing the singer to shout at and slap at the various men she sits down with. For modern spectators, it is perhaps clearer that such a joke primarily works for male viewers; female audience members may find little to laugh at here. This indicates that Formby’s primary appeal was to men, whereas Gracie Fields aimed her jokes and songs at a broader audience.

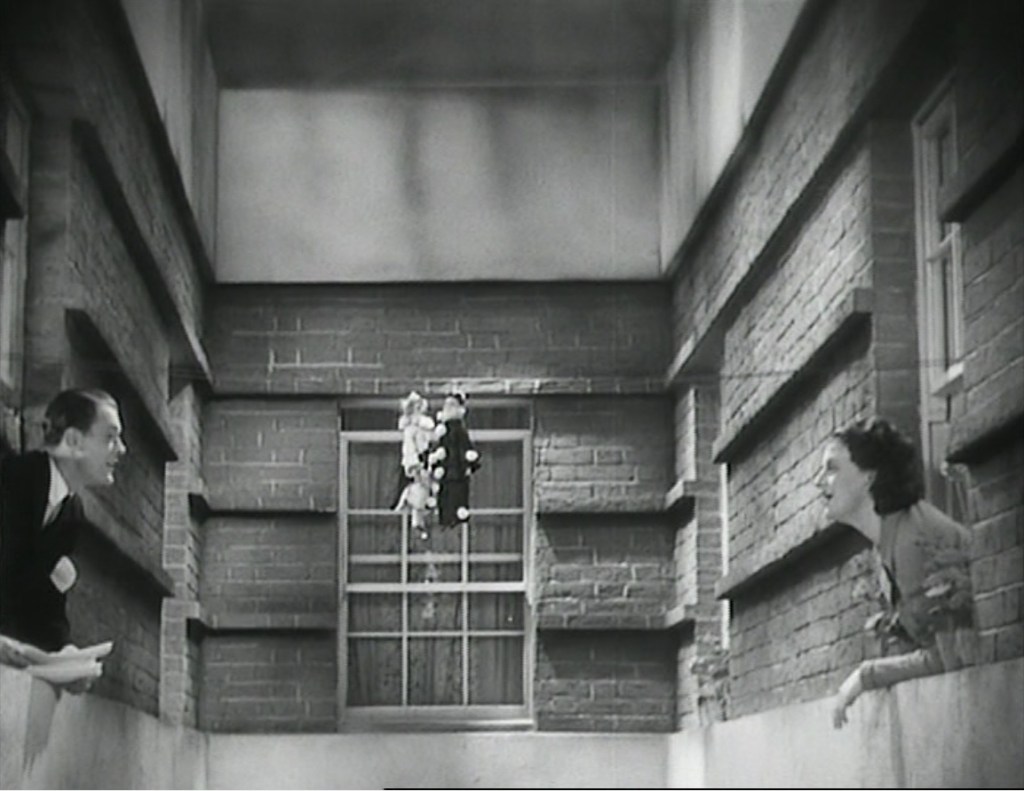

Trouble Brewing ends in the beer brewery where the gang is hiding. Here physical comedy takes over, with actors running up and down stairs, hiding in barrels, and hanging on ropes. The brewery contains several vast vats of beer, which are left uncovered. Bill lands in one and becomes inebriated almost immediately; the same eventually happens with the counterfeiting gang members. The apparently instantaneous effects of alcohol on the men underlines how far the events on screen are removed from reality at this stage of the film. It has developed into slapstick, harking back to earlier cinematic traditions.

Unlike another 1939 film set in a brewery, Cheer Boys Cheer, which makes direct reference to Nazi Germany, Trouble Brewing offered audiences complete escapism. Money laundering and the circulation of counterfeit money were popular tropes in interwar crime fiction, but they were far removed from the real-life horrors of war and fascism. The film expanded on the already-established cinematic narrative that journalists could effectively solve crimes, by presenting three workers as skilled detectives. The film’s happy ending no doubt provided audiences with welcome escapism as the international political situation deteriorated.