By 1926, cinemagoing was firmly established in Britain, and it was transforming from a working-class hobby to something rather more respectable. Super cinemas, which offered lounges and tearooms as well as screenings, were designed to attract middle-class women. Film historian Ina Rae Hark has argued that cinemas tried to draw in female customers by “attempting to create a dream home in which the woman could (…) enjoy complete freedom from responsibility for its maintenance.”[1] Like the department stores that appeared in Britain at the end of the nineteenth century, super cinemas gave women a respectable place to go when they were out in town: a female equivalent for male clubland.

Inside the screening room, audiences did not just see a single film, but rather a varied programme of features, cartoons, informational films and advertisements. In 1926, silent film director A.E. Coleby, who had previously directed morality tales such as The Lure of Drink (1915) produced a series called Hints and Hobbies. Twelve episodes of this weekly bulletin survive in the BFI National Archives and are available to view online for UK-based audiences. These amusing films provide insight to the range of topics which were deemed relevant and suitable to a largely female audience.

Each episode of the series is about fifteen minutes long and covers a series of topics for a few minutes each. The very first Hints and Hobbies starts with a ‘Pets Column’ featuring kittens and puppies, showing that a version of the cat video has been a crowd pleaser for over a century. It then moves to a woman demonstrating how you can make a large decorative vase out of cardboard – for the use of dried flowers only one presumes! It is introduced with the title: ‘An Interesting Hobby which can be made to help pay the rent (?)’ It is evidently not going to be the most effective way to earn extra cash, but this does show that the target audience for this segment are women who are not poor but still could do with some more disposable income.

The penultimate sketch included in episode one is clearly aimed at the same audience. Titled ‘If only husbands were like this!’, it shows a married couple at the breakfast table. The woman receives a number of bills for recent clothes purchases: £8 8s for two hats, £10 10s for a ‘costume’, and £21 for an evening dress. This was serious money in 1926, but the fictional husband is unperturbed. ‘Quite alright, darling’, he says, and even says his wife should have treated herself to a second gown. E.M. Delafield’s Provincial Lady, no stranger to the lure of the boutique and the subsequent bank overdraft, would no doubt have appreciated this scene.

Hints and Hobbies also reflected modern concerns of the time, such as road safety. As this blog has noted previously, the interwar period saw a huge increase in car ownership but little in the way of safety regulations. In lieu of driving licenses or instructors, poor driving was rife. The first episode of the series exhorts drivers to be mindful of others when overtaking one another; the second episode asks female drivers specifically to not be ‘Miss Kareless Kornerer’ when taking a left-hand turn.

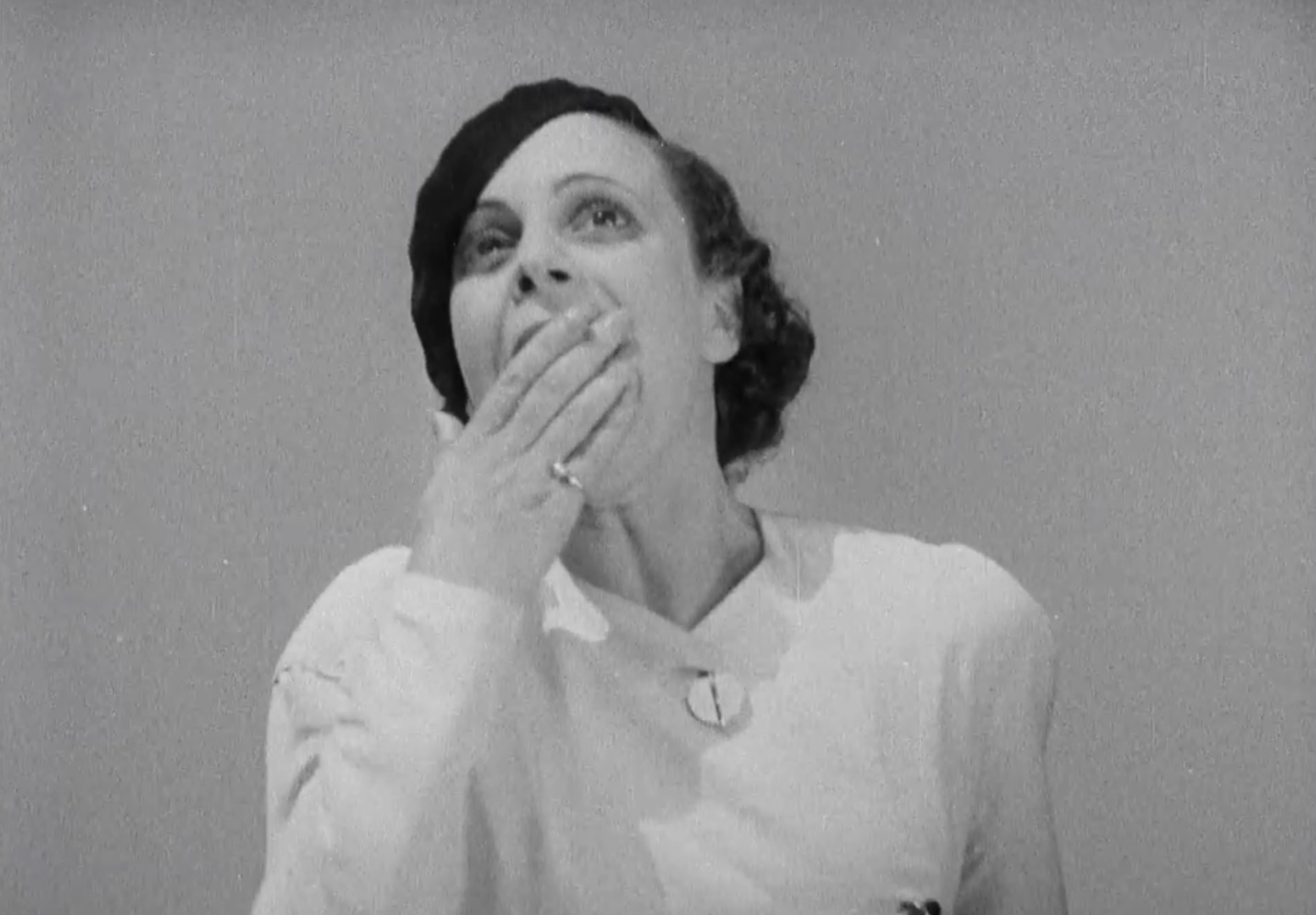

Along with the household and cooking tips included in each episode, Hints and Hobbies also took the traditionally feminised profession of nursing and used it to teach first aid to a wide audience. Lady Superintendent Mrs Webb from the St John’s Ambulance Brigade was on hand to demonstrate how to dress a wound in the palm of one’s hand, or how to make a splint for a fractured leg. Seven years after many women had trained as nurses during the First World War, these segments taught a new, younger generation of women the principles of emergency care. Mrs Webb appears in her uniform, capably handling the tools of her trade to fix up male patients.

The penultimate surviving episode of Hints and Hobbies veered away from accepted femininity and treated its audiences to something rather more transgressive: jiu-jitsu for women. The alarmist intertitle ‘You never know when the following may happen to you’ is followed by a sequence showing a young woman being attacked by a male loafer, who tries to steal her handbag. Luckily for the victim, a capable female motorist steps out of her car, grabs the man, retrieves the handbag, and ends with throwing the attacker to the ground. When returning the bag to the first woman, she tells her ‘My dear, it behoves every girl to-day to be able to protect herself…If you will come to the address I will give you at 7 o’clock to-night I will give you a few hints.’

It’s no surprise that this particular episode of Hints and Hobbies has been embraced by some LGBTQ viewers as representing an example of ‘lesbian erotica.’ Dressed in short tunics and standing on mattresses, the two women demonstrate several self-defence moves on one another. This no doubt also gave straight male viewers plenty of ‘visual pleasure’ but the casting of the man as the villain rather than hero in this segment, and a final shot of the two women embracing and leaving the room with their arms around one another, give plenty of space for a queer reading.

Little else appears to be known about Hints and Hobbies – who decided which topics to include, which cinemas they were shown at, or why the series did not last. However, even without any additional information the series provides plenty of insight into what the producers thought would entertain and inform their mostly female audiences. The changing gender norms of the period are reflected in the content that veers from tips on how to remove ink stains from aprons to improvising fancy dress for your next flapper party.

The full Hints and Hobbies series can be viewed for free by UK-based viewers on the BFI Player.

[1] Ina Rae Hark, ed, Exhibition: The Film Reader (London: Routledge, 2001), chapter 12, Ina Rae Hark, ‘The “Theatre Man” and the “Girl in the Box Office”, pp. 143-154 (p. 145)