A recent trip to an antique shop delivered a great find: a complete album of film star cigarette cards, collected and collated some time in early 1934. Cigarette brands regularly put out series of cigarette cards, which young people could collect and paste into dedicated albums. In 1934, John Player & Sons, a branch of the Imperial Tobacco Company, published a 50-card series of portrait drawings of film stars. The reverse of each card had some information about the actor. All cards could be pasted into an album; the information that appeared on the reverse of each card was reprinted on the album pages.

My copy was put together by John MacLaren, who lived in Addison Gardens (between Shepherd’s Bush and Kensington Olympia) in West London. We can assume that John was a big film fan as the album is complete, all the cards are inserted into the album neatly, and he handled the album carefully. Nearly 90 years after its composition, it is still in excellent shape with very little wear and tear. The album reveals aspects of 1930s British film fan culture to us: which stars were included, what biographical information was included on them, and which stars were left out?

The first thing to note is that this album is all about the ‘film stars’: there is virtually no mention of directors or producers anywhere in the album. An exception is the entry given for Greta Garbo, which notes that producer Joseph Stiller, upon being given a Hollywood contract, took Garbo ‘along with him’ to the US. The entry for Jessie Matthews, however, makes no mention of Victor Saville, even though she had regularly worked with him by 1934. Similarly, under Marlene Dietrich’s picture there is no mention of Joseph von Sternberg, even though the pair had successfully collaborated several times at this point. Film fan culture in the interwar period was all about the ‘stars’ which appeared on the screen: although retrospectively directors like Hitchcock, Korda and Asquith are recognised as masters of the form, in the interwar period audiences would have been unlikely to seek out a film on the strength of its director alone.

The focus on ‘stars’ rather than ‘actors’ also means that the album mostly contains young, good-looking actors, although a few British ‘character actors’ are included. There are 30 female actors and 20 male actors included; although images of female stars were generally considered more commercially attractive, the album shows that male actors were by no means unimportant and could have considerable ‘sex-appeal’.

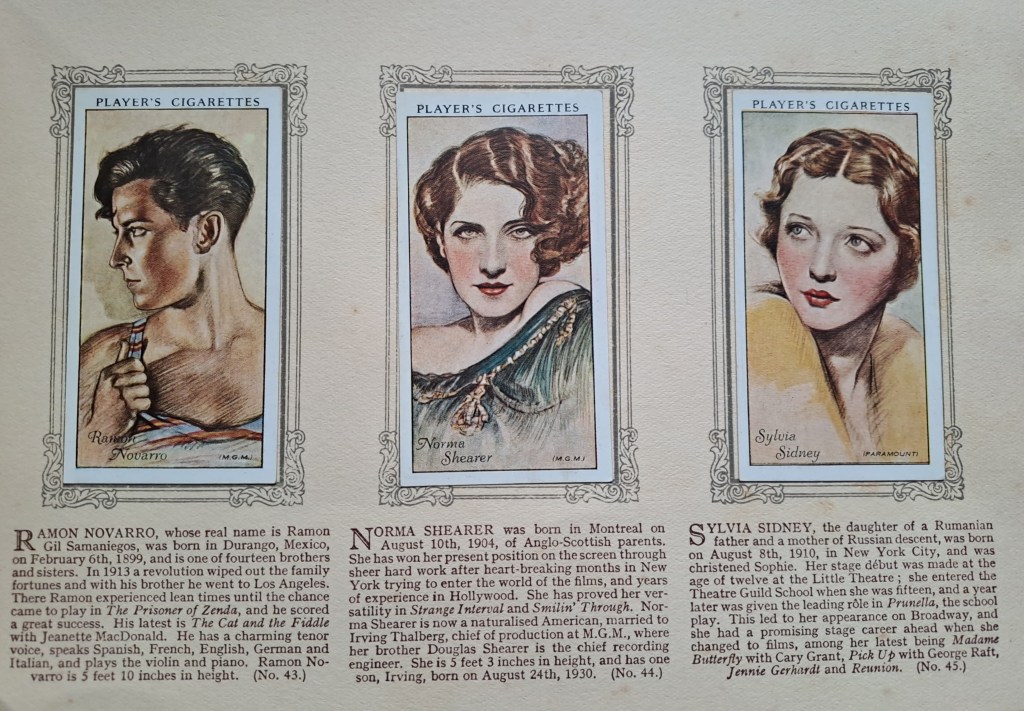

Some of the text descriptions, particularly those of male actors, include their height. This was clearly deemed to be important information for the film fan. The description of Johnny Weissmuller thus reads ‘The Olympic Swimming Champion, who stands 6 feet 3 inches in height, made his screen début in short sports films, and because of his magnificent physique was given the title role in Tarzan the Ape Man.’ Even if one had never seen a Johnny Weissmuller film, this description is graphic enough to let the imagination run wild. The drawing of actor Ramon Novarro (5 feet 10 inches) shows him in a vest top which he is tugging slightly to reveal his chest. His Mexican heritage no doubt played a part in this exoticized depiction: virtually all other male stars are shown wearing a suit.

Out of the 50 actors included in the album, 29 are American, 11 are British, and the remaining 10 are from other countries – mainly European, but it also includes two Mexicans, a Canadian, and one star born in China to white expat parents (Sari Maritza ‘Her father was English, her mother Viennese’). ‘Talkie’ films were well-established by 1934, and the album shows that although the transition from silent to sound film had limited the international opportunities for non-native English speakers, it had not completely removed them. The aforementioned Garbo and Dietrich were celebrated for their European appearance and demeanour – and both had a powerful male industry figure supporting them. The range of actors included in the album also shows the popularity of Hollywood films in Britain, despite the British government’s attempts to boost the domestic film industry. American stars continued to exert their influence over British fans.

British actor, producer and race-horse owner Tom Walls

Another reason for the popularity of film stars can be found in many of the narratives that accompany the pictures. Although they are only a short paragraph each, a significant number of them present the careers of film stars as being reached almost by accident. American star Jack Holt, for example, is described as having been ‘in turn a civil engineer, a prospector, a mail carrier in Alaska, a cow-puncher [a cowboy], and finally an actor.’ Madeleine Carroll first worked as a school teacher before taking to the stage; Frederic March was a bank clerk; and Robert Montgomery worked ‘in a mill, then on an oil tanker, and finally became prop man in a touring company.’ The implication is that it is possible to move from a blue-collar or white-collar job into film stardom, and that such a move may be open to the film fan collecting the cigarette cards. This reiteration of the humble origins of many stars, and the supposed open entry to film acting, was an important part of the film industry’s myth-making that constantly held out the possibility to fans that they too could join their favourite stars on the silver screen.

We have no way of knowing whether John Maclaren, the owner of this particular album, had any aspirations to become an actor. Nonetheless, the survival of this album and the care John took in pasting in the cards demonstrates how important film fandom was for him, as it was for thousands of other (young) people in Britain at the time. The cigarette cards gave film fans another accessible way to connect with their favourite actors, in addition to going to the cinema and reading fan magazines. It stands as a testament to (commercial) fan culture in interwar Britain.