As the UK prepares for the first coronation since 1953, it is a good opportunity to look back on the only coronation which took place during the interwar period. On 12 May 1937, King George VI was crowned in Westminster Abbey. Initially, it had been planned that the coronation that day would have been of Edward VIII, but after the Abdication Crisis of late 1936, it was decided to use the same date for a different coronation ceremony.

Although the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II was famously the first national ‘TV event’ in Britain (there’s even a Dr Who episode about it), new media were also used for the coronation in 1937. The last coronation before this year had been in 1911, when moving image mediums were still in the early stages of development. In that year, silent film footage of the procession was recorded from static cameras, mostly at a remove from the action. By 1937, sound cinema was omnipresent, and making a filmed record of the coronation was an integral part of the day. A film of nearly an hour was recorded, which included many shots taken inside Westminster Abbey during the service. The whole was overlaid with an informative voice-over explaining the action.

Although a large number of people, possibly up to a million, travelled to London to witness the procession, there were many more subjects who would not have been able to see this royal ceremony in person. These were not just in Britain, but across the world. As one local newspaper put it, ‘figuratively waiting upon the Throne and its new King to-day were the 500,000,000 people of the Empire.’[1]

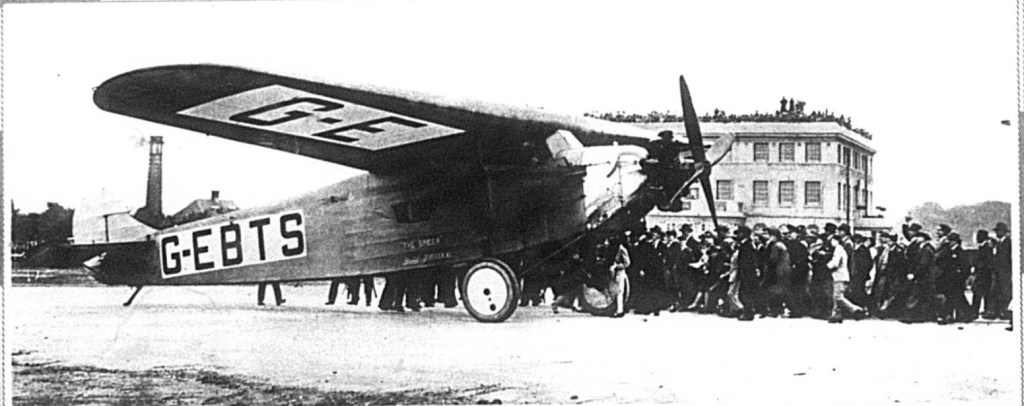

The distribution of the coronation film was one of the key strategies to ensure that these half a billion people could feel a connection with the new monarch. The film was edited and distributed quickly – only two days after the coronation, on Friday 14 May, people in provincial towns such as Gloucester were able to see ‘The Great Coronation Film: The House of Windsor.’ It was advertised as including ‘THE ACTUAL CROWNING CEREMONY IN THE ABBEY’. In the case of Gloucester, it was showing in three different cinemas with each screening it four times a day.[2]

Other mass media were also used to create a sense of a community of subjects. Arguably, the fact that until six months before the coronation no-one had expected this second son to become king, made it likely that most people in the country had only a very limited understanding of who their new King was. Local newspapers printed articles setting out details about the new King and Queen, to inform their readership. The Lancashire-based Nelson Leader told its readers that for the new King, ‘Duty is a quiet passion with him, as it was with his father.’[3] Multiple newspapers assert that the King’s main interests are the nation’s industry and support for young people – both uncontroversial topics. The other key feature that papers highlighted was the domestic bliss of the new royal couple: ‘Ideally happy has been the married life of King George and Queen Elizabeth’; and most articles also describe the couple’s daughters in flattering terms.[4]

The spectre of King Edward VIII is mostly in the background of these reports; but in the Derbyshire Times he is evoked explicitly: ‘King George lacks some of the qualities that inspired high hopes of King Edward VIII – he is more reserved, more conventional, and makes friends less easily – but he has certain qualities that his more brilliant brother lacks: he is steadier, less impulsive, more persevering, and more dutiful.’[5] And, of course, the new King’s steady family life is infinitely preferable to a King married to an American divorcee, although none of the newspapers make that explicit.

A final strategy employed to create an ‘imagined community’ of subjects around the new King is the issue of special coronation stamps. These went on sale on the day after the coronation, and multiple papers reported that there was a record interest in them. ‘Queues formed at many post offices and for the first time special stamp counters dealt with the rush. Arrangements had been made for the sale of 38 millions.’[6] Stamps, bearing the image of the new monarch and uniquely linked to national identity, are another tactic to reinforce to the audience that they are part of a defined group of royal subjects.

So, beyond the actual coronation ceremony itself in London, which saw ‘[m]ore than 5,669,000 passengers (…) carried by the London Underground Railways during the forty-six hours of continuous service’; ‘200 tons of litter (…) removed from the three miles of the Coronation route and side streets’; and a 6.5 mile procession through Westminster, modern mass media methods were used to ensure that the coronation’s impact reached to all corners of Britain, and beyond that through the Empire.[7] After the unprecedented events of the Abdication, which had the potential to damage the crown, the coronation was used to reinforce the monarchy as a stable and positive influence.

[1] ‘Happy and Glorious’, Lincolnshire Echo, 12 May 1937, p.6

[2] Cinema adverts, Gloucester Citizen, 14 May 1937, p. 11

[3] ‘Long May They Reign!’, Nelson Leader, 14 May 1937, p. 6

[4] Ibid.

[5] ‘King George VI and his coronation’, Derbyshire Times, 14 May 1937, p. 30

[6] ‘Rush to buy new stamps’, Daily News, 14 May 1937, p. 8

[7] ‘King and Queen thank the nation,’ Liverpool Echo, 14 May 1937, p. 11; ‘Long May They Reign!’, Nelson Leader, 14 May 1937, p. 6