This is the fifth in a 11-part investigation into the 1934 ‘Bow Cinema Murder’. You can read all entries in the series here.

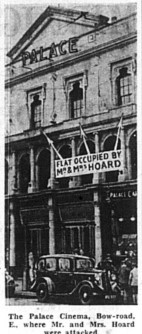

When Dudley and Maisie Hoard were found, critically wounded, around 8.30am on 7 August 1934, the first police officer on the scene was PC Duncan Mackay. He was patrolling the local area at the time, and was therefore able to get to the cinema quickly. PC Mackay was part of the army of patrolling Bobbies who worked all over London, each walking their regular ‘beat’ so that they could be on hand if anyone in the neighbourhood needed police assistance. After arriving at the cinema, PC Mackay quickly rang his local station for back-up. The Metropolitan Police had divided London in a series of divisions; Bow Road was part of ‘H’ Division, which covered the wider Whitechapel area. There were a few police stations near the cinema – Bow Road station was the closest, but there was also a station at Arbour Square, a short distance away.

Each police division had a team of detectives: plain-clothes officers who were tasked with investigating crimes and tracking down criminals. In addition, there was the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), commonly known as Scotland Yard. This team worked across all of London and specialised in the most difficult crimes, as well as criminal activity that was not confined to one area – for example, during the 1920s Scotland Yard spent a fair amount of time investigating crooked racecourse betting gangs.[1] Working for Scotland Yard was prestigious, as the small team often dealt with high-profile cases.

After PC Mackay’s phone call, the first officers to arrive at the cinema were the detectives attached to ‘H’ Division. Most of these men were born locally, and they would spend many hours over the next weeks to not only catch the murderer, but also put together sufficient evidence to ensure a conviction. In the interwar period, the police’s remit was wider than it is today, and the police took on some tasks which would now sit with the Crown Prosecution Service. Detectives were responsible for ensuring that all the evidence fit together and made a convincing court case. This meant that even after a criminal was caught, they would still have significant work in (re)interviewing witnesses, tying up loose ends, and getting additional expert opinions.

The detectives who were the first to arrive at the cinema were Detective Sergeant James Rignell, a 34-year old born in Poplar who had joined the Met shortly after the First World War; Detective Inspector Henry Giddins, who had only been promoted to this rank less than a week before the murder took place; and Detective Sergeant Claud Smith, who was born in Mile End and also joined the police immediately after completing his First World War service. Between them, they started a physical investigation of the murder scene and questioned the cinema staff who had started to arrive for their shifts. James Rignell went to the hospital and took the very first statement from Maisie Hoard.

Very quickly, a decision was made that Scotland Yard needed to be involved in the investigation. The attack had been brutal, and DI Giddins was very new to his role. Around 3pm on the same day, Detective Inspector Fred ‘Nutty’ Sharpe of Scotland Yard arrived at the cinema. He would be in charge of the investigation from that point onwards, leading the ‘H’ Division team and drawing on staff in other parts of London as needed. As it transpired, the investigation would lead the police out of London to the Norfolk/Suffolk borderlands, and Sharpe’s position in the CID gave him the authority to instruct police forces outside of the capital, too.

Fred Sharpe had joined the Metropolitan Police in 1911, and spent most of the first decades of his police career chasing criminal gangs, pickpockets and car thieves. In his memoirs, which he published in 1938 after his retirement, he advocated that police detectives should cultivate friendly relations with professional criminals. He argued that there was a reciprocal relationship and a level of respect between criminals and the police, in which both groups knew the rules of the game they were involved in. This approach got him in hot waters after his retirement, when Sharpe himself came under police investigation for engaging in bookmaking activities.[2]

Murder, however, appears to have been a separate category for Sharpe. He devoted an entire chapter to the Bow Cinema Murder in his memoirs, in which he referred to the murder as ‘one of the most savage a man has ever committed.’[3] He underscored this supposed savagery by describing his physical reaction to the crime scene: “The flat itself and the hall presented a horrible and ghastly scene, showing that the utmost violence had been used in the attack on this unfortunate couple. (…) the sight of that room and the passageway nearly made me sick.”[4] Sharpe ensured that the details of the crime scene were captured by ordering a police photographer to attend the scene on the day of the murder. These photographs show copious amounts of blood on the staircase where Dudley was found, as well as the blood-soaked bedsheets which Maisie had left behind.

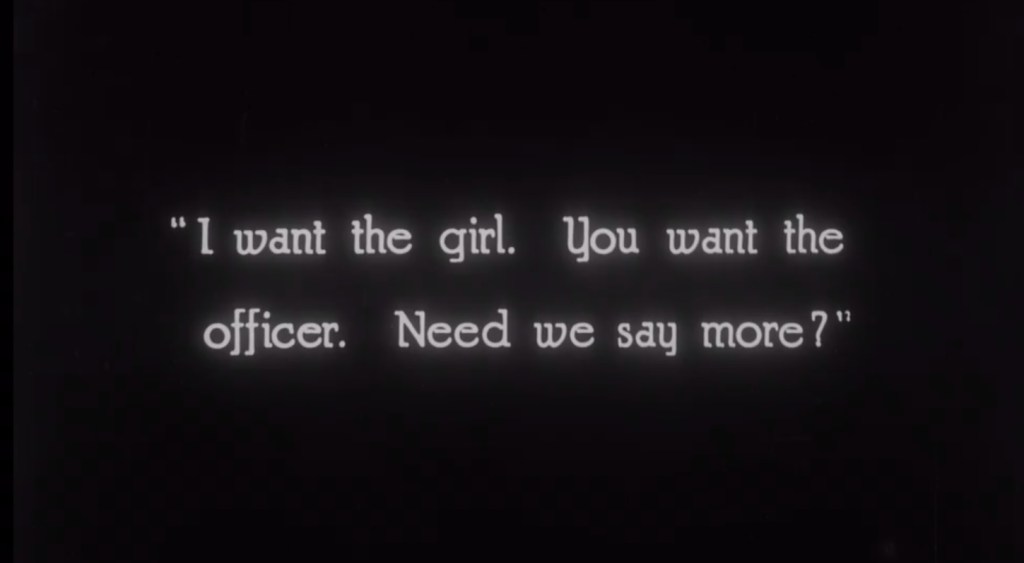

At the close of 7 August, the police did not yet have any clear leads. The staff who had been arriving at the cinema had not been able to share much useful information. Most of the crimes they investigated were committed by criminal gangs, and this guided their initial thinking. Newspaper reports stated that the police were speaking to their contacts in criminal gangs to gather information – using that network which Fred Sharpe often relied on.[5] Police officers remained stationed at the cinema overnight, and some materials had been taken away for forensic examinations. It was not until the next day, however, that a clear suspect would emerge.

[1] Heather Shore, ‘Criminality and Englishness in the Aftermath: The Racecourse Wars of the 1920s’, Twentieth Century British History, vol. 22, no. 4 (2011), 474-497

[2] ‘Ex-Chief Inspector Sharpe of the Flying Squad: bookmaking activities under the name of Williams’, MEPO 3/759, National Archives

[3] Frederick Sharpe, Sharpe of the Flying Squad, (London: John Long, 1938), p. 126

[4] Ibid., p. 127

[5] ‘“Yard” reconstructs the crime,’ Daily Herald, 8 August 1934, p. 2