The 1920s were a turbulent time for Britain, both at home and abroad. The decade saw the beginning of the end of the British Empire, as Ireland and Egypt gained a level of independence in 1922. Throughout the 1920s popular support for independence grew in India, with Ghandi’s Non-Cooperation Movement founded in 1920. At home, as in the rest of Europe, ideological and extremist political factions gained support. The British imperial identity was clearly under threat during this period.

The Royal Family, as the figureheads of this imperial identity, worked hard to reaffirm conservative values and traditions and bolster a sense of national cohesion. They used cinema as one of the ways in which to promote the Empire and their own role in maintaining it. In the 1920s the King, Queen and Prince of Wales interacted with cinema both as consumers and as subjects of films. By engaging with cinema, the Royal Family both shared in a common activity which appeared to bind them together with the general public; and set themselves apart as extraordinary figures whose importance enabled them to appear on the silver screen.

The Prince of Wales was a subject of films that were made of his various Tours of the Empire which he undertook in the 1920s. He visited New Zealand in 1921, India in 1921-22, South America in 1924 and South Africa in 1925. These tours were routinely filmed, and the films were screened in British cinemas. At their initial release the films usually premiered at the Marble Arch Pavilion and the Stoll Picture Theatre on the Kingsway, before being distributed more widely. On 12 May 1925 more than half of The Times’ regular ‘The Film World’ column is taken up by a detailed description of Part 1 of the Prince’s Tour of Africa film, which gives an indication of the importance these films held at least for the Empire-minded Times.[1]

These Tour films placed the Prince of Wales as inextricably connected with the Empire, in the popular imagination. For the general public, the Prince was frequently visible as visiting all the corners of the Empire, reasserting his Royal authority over citizens across the globe. The images and intertitles of the films show how the texts consciously stress the coherence and common experience of Empire. In the newsreel summary of the Prince’s Tour of South America, when he visits a group of war veterans, the intertitle confidently states that ‘There are few cities under the sun that cannot raise a muster of British ex-servicemen.’ Empire here is emblematised in the image of the war veteran, who risked his life and health in order to maintain the integrity of said Empire.

Apart from the Prince of Wales’ tours, the Royal Family was also subject of a number of feature length films. In 1922 Cecil Hepworth produced Through Three Reigns, a compilation film which consists of footage of the Royal Family between 1897 and 1911, as well as extracts from actualities and other early cinema footage. Hepworth updated his efforts in 1929 with Royal Remembrances, which was also a compilation of footage of the Royal Family but this time the most recent footage was of 1929.

On 25 September 1922 the King and Queen asked for a special ‘command’ performance of Through Three Reigns at Balmoral Castle. This event was widely reported in the press.[2] The Royal couple invited 200 guests, including their tenants and servants, to attend the screening where they effectively watched their own family history. Shown in conjunction with Through Three Reigns – and different newspapers give different weight to this – was Nanook of the North, the ground-breaking Inuit documentary made by Brit Robert Flaherty. In one evening, the King and Queen watched a film that reasserts the significance of the Royal Family, and a film which demonstrates the technological and geographical advancements of the British Empire. This was the third of such ‘command’ performances that year – at an earlier screening at Windsor Castle the King and Queen had asked for the Prince of Wales Tour of India film.

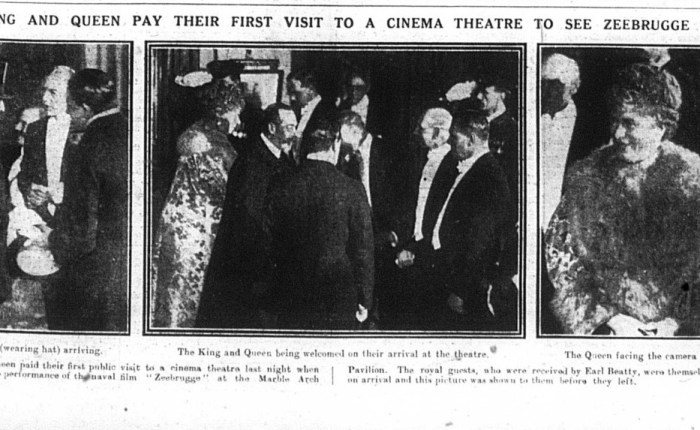

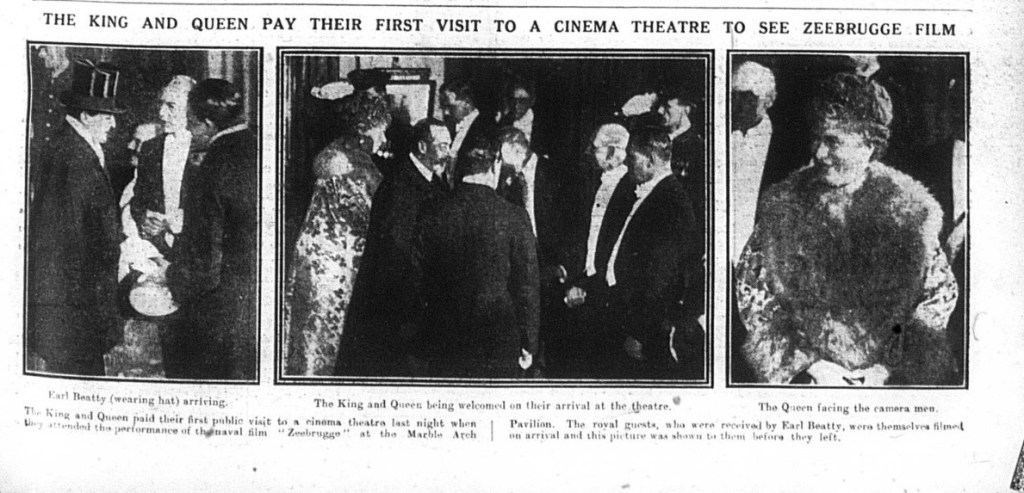

The King and Queen’s first public visit to a cinema came two years later, in November 1924 on the eve of Armistice Day. The occasion was a charity screening to raise money for the newly formed British Legion. The royal couple saw the non-fiction film Zeebrugge, which told the story of the British army’s attempt to close off the Belgian port of Zeebrugge during World War One. Again the event was covered extensively in the press.[3] Crowds cheered the Royal Couple as they arrived at the Marble Arch Pavilion and were shown to the Royal Box which was constructed for the occasion. Three commanders who had received Victoria Crosses for their bravery during the Zeebrugge Raid were also in the audience.

The Daily Telegraph gave a detailed report of all the aristocrats who attended the screening. The cinema space, normally open to audiences of all backgrounds, on this occasion became a much more exclusive space. It seems that the King and Queen could endorse cinema, as long as cinema related to serious and inoffensive topics –and the films they viewed were British productions, of course. The Royal’s support of cinema underscored the Royal Family’s values: of course the King and Queen saw films like everyone else, but only those that promoted the national identity of their country, and those that would not cause offence to any of their subjects.

During the visit to the Marble Arch the Royal Family also became the subject of a novel technological experiment: their arrival at the cinema was filmed, and while they were watching Zeebrugge the film was developed, and played back to the audience at the end of the evening. The Royals became subject of a film which they later consumed as an audience. This circularity was also demonstrated in the private Royal screenings in 1922: one of the topics that the Royal family could watch without risk of controversy was – the Royal family.

By the end of the 20s, film had become a recognised medium to promote empire, either directly through ‘educational films’ or indirectly by using cinema screenings to raise money for charities with Royal patronage. In this decade, the Royal family had gotten involved in the cinema business, and started using it as a means of increasing their popularity and profile, and of reaffirming discourse on empire and nationalism. Although the cinema could be a democratic space, the Royal Family’s interactions with it were carefully constructed. This way, they cleared the way for later generations of Royals to use popular entertainment to maintain the ‘common-sense’ status quo of monarchy.

Through Three Reigns is available to watch for free on the BFI Player (UK only)

[1] ‘The Film World’, The Times, 12 May 1925, p. 14

[2] ‘The King Sees Himself’, Daily Express, 26 September 1922, p. 7; ‘Royal Family Film’, Daily Mail, 26 September 1922, p.6; ‘Films at Balmoral Castle’, Daily Telegraph, 26 September 1922, p. 12; ‘Royal Ballroom Cinema’, Daily Mirror, 26 September 1922, p. 2

[3] ‘King and Queen at the Cinema Theatre’, Daily Telegraph, 11 November 1924, p. 11; ‘King and Queen See Zeebrugge Film’, Daily Mirror, 11 November 1924, p. 3; ‘The King & Queen Filmed’, Daily Mail, 11 November 1924, p. 7