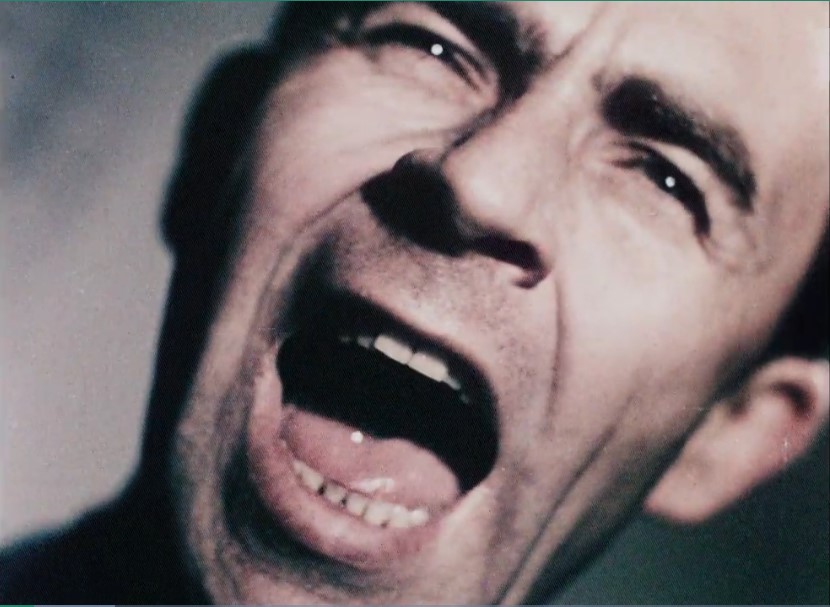

On the eve of the Second World War, Associated British Picture Corporation produced Murder in Soho, a gangster flick starring American actor Jack La Rue (not his real name, obviously). The presence of Italian-American La Rue, with his cleft chin and strong jawline, brings Hollywood glamour to what is otherwise a crime film with an extremely thin plot. Murder in Soho appears to be a solitary British outing for the actor, although he did take the opportunity to get married whilst visiting London for the film’s shooting.

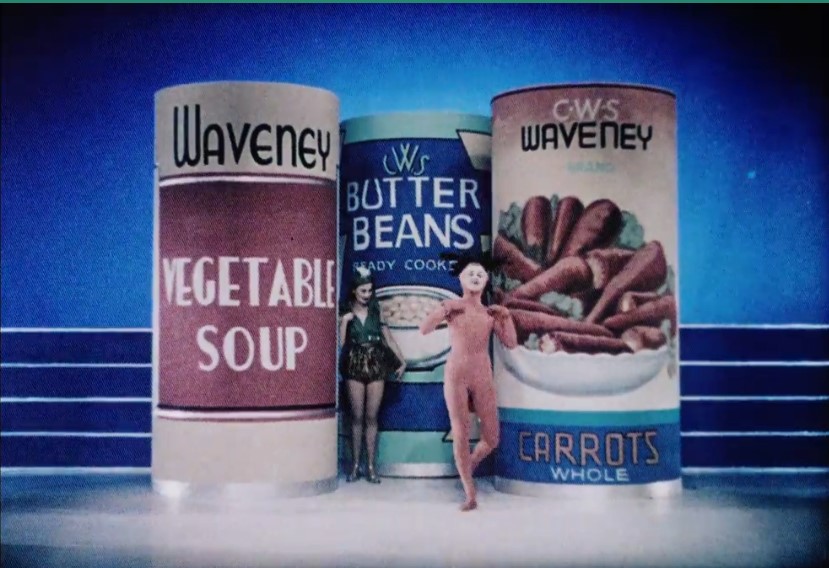

Like the almost contemporaneous They Drive By Night, Murder in Soho works hard to incorporate American slang into its dialogue, presumably to appeal to younger audiences. They Drive By Night, however, was produced by the British arm of American studio Warner Brothers. Murder in Soho comes from a British production company that was Hitchcock’s home for many of his silent films including Blackmail (1929); Murder! (1930)and The Skin Game (1931). Alongside these British thriller/crime films, ABPC (which previously operated as British International Pictures) also produced musical films such as Harmony Heaven (1930) and Over She Goes (1937). They did not have a strong background in producing American-style crime films – and it shows.

The plot of Murder in Soho is extremely thin. La Rue plays nightclub owner Steve Marco, who runs the ‘Cotton Club’ in Soho. He has just hired a new singer for the club, Ruby Lane. Steve is interested in Ruby as he thinks she has ‘class’. He doesn’t know, however, that Ruby is married (but separated from) Steve’s British associate Joe Lane. When Joe betrays Steve and steals £2000 off him, Steve kills Joe. Soon police inspector Hammond comes asking questions. He recruits Ruby to work with him and reveal Steve’s criminal activities. Also in the mix, although largely superfluous to the plot, are a journalist called Roy Barnes who frequently visits the club and falls in love with Ruby; Steve’s ex Myrtle who he has dumped in favour of Ruby; and performing duo ‘Green and Matthews’ who also work at the club.

Murder in Soho contains all the popular elements of a 1930s crime film: a nightclub; an international criminal gang; a singer; a police inspector; a journalist. Yet these elements are not fused together with a compelling plot or livened up by any original ingredient. Indeed, the film’s insistence to try and introduce Americanisms into the narrative detracts even more from the action. Steve and his henchmen speak in thick Italian-American accents. The character ‘Lefty’ in particular, who is the young comedy sidekick, litters his dialogue with references to ‘dames’ and ‘cops’. The name of the club obviously refers to the famous Harlem nightclub – but there were no British Cotton Clubs and the name does not have the resonance in Britain as it would do in the United States. Steve employs Black bartenders in his club – again a practice which was much more common in the States than it was in Britain. Compared to depictions of nightclubs in other British films of the 1930s, the Cotton Club in Murder in Soho feels more like a replica of a Hollywood set than of anything resembling British nightlife.

The very opening of Murder in Soho also presents a version of Soho that was much more deliberately criminal and seedy than what is usually presented in British films. Familiar shots of the neon lights of Piccadilly Circus are interspersed with a close-up shot of a roulette table; a shot of an underground dive bar; and a shot of two prostitutes propositioning a man in an alleyway. Unlike the majority of British films of the period, which worked to preserve an image of London and Londoners as ultimately adhering to the law and to a high moral code, Murder in Soho explicitly positions Soho as a criminal space. Granted, the main criminal element in the film is foreign, but Joe Lane is British, as is Myrtle, Steve’s scorned ex who ends up killing him. Soho here is a lot seedier than the Soho portrayed in, for example, Piccadilly (1929).

Rather surprisingly, then, Murder in Soho also contains plenty of comic notes, and a few secondary characters who are only included to provide comedy relief. Most notably, the performing duo Green and Matthews, which weave throughout the narrative. Lola Matthews is portrayed by Googie Withers, who this early on in her career already had made a name for herself as an excellent comic actress. As Lola she patters on non-stop, innocently flirting with every man and completely oblivious that her dance partner Nick Green is besotted with her. A frequent club visitor whose role is simply credited as ‘Drunk’ provides diversion in scenes when he tries to eat with chop sticks or enters the dancefloor for a solo performance. These interludes do undercut the drama and suspense that the film attempts to create at other points.

Murder in Soho is a late-interwar curiosity – a film that tries to appeal to British audiences by inserting American glamour; a film that tries to be both serious and funny at the same time; and that ends up feeling like a painting-by-numbers effort that adds up to less than the sum of its parts.