With the summer season upon us, many may be planning to head off for a few weeks to relax on holiday. The right to paid holiday these days is enshrined in UK law. The first legal intervention in this area came in 1938 with the Holidays With Pay Act. Rather than setting out an inalienable right to holiday, however, the purpose of the act was to ‘enable wage regulating authorities to make provision for holidays and holiday remuneration for workers whose wages they regulate, and to enable the Minister of Labour to assist voluntary schemes for securing holidays with pay for workers in any industry.’ It was facilitative rather than prescriptive, giving employers a framework for offering paid holiday if they wanted to do so. Even for those covered by the Act, they would only receive one week of paid holiday a year.

Prior to 1938, there was no legal concept of a holiday in Britain. What’s more, the ‘weekend’ for most of the interwar period comprised only Saturday afternoon and Sunday; this 5.5 day work-week had developed in the 19th century. Bank Holiday weekends (where the Monday was a national holiday) could be the only extended break a working person had. The notion that workers should be entitled to extended time off work whilst still receiving pay was not commonly held. At the other end of the social spectrum, the upper classes were generally not in wage-earning roles and therefore had much more freedom over how they used their time.

What were the options for breaks, then, for different social groups during the interwar period? At the lower end of the social scale, East End workers could go to Kent in the summer months to go hop-picking. This was not a holiday as such as they would still be required to undertake long hours of manual labour, but it gave an opportunity to leave the city and enjoy the countryside. They would also get paid for their efforts and be given lodgings by the farmers. George Orwell went hop-picking in 1931 during one of his expeditions moonlighting as an iterant worker. He describes the communal aspects of the picking, with whole families coming down and picking together. The 1917 film East is East includes extensive scenes on Kent hop-picking fields as the main character makes her way there for a summer job.

Hop-picking was not a holiday, but rather an opportunity to undertake seasonal work and escape the squalor of London during the hottest months. If you had slightly more disposable income, a day-trip could be a welcome activity. The cheapest and most comfortable way to travel would be by charabanc (an early type of motor bus); either by buying a ticket on a scheduled service or by pooling together as a community group and hiring a private coach.[1] The proximity of a range of seaside towns to London made them a popular choice of destination for these trips; then, as now, many seaside towns offered entertainment on the pier and quayside.

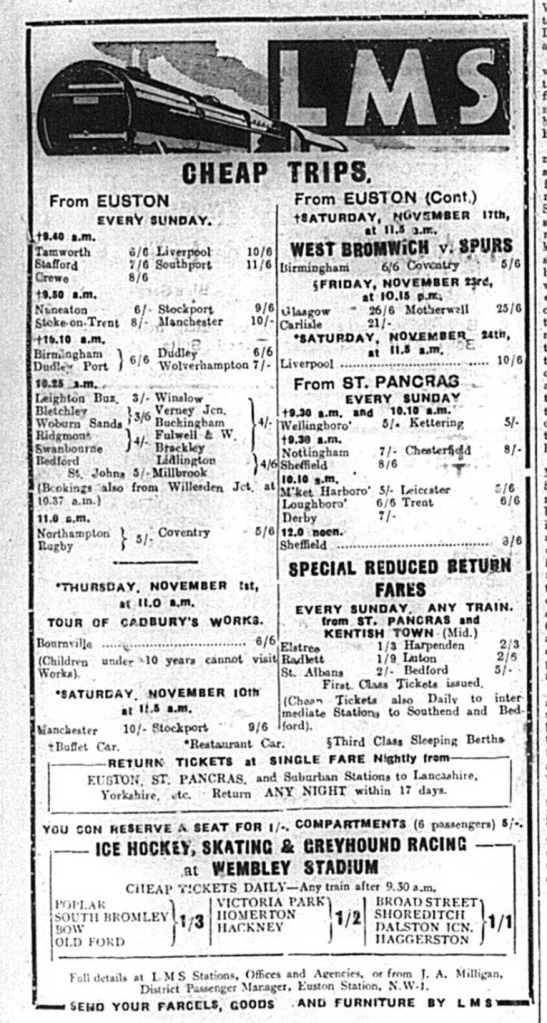

For those able to spend a bit more, travelling by train allowed access to a much larger part of Britain. By the interwar period, Britain’s rail network was mature and there were numerous London terminals from which to board trains. Train operators advertised ‘cheap trips’ in London newspapers. For example, this 1934 advert from the London, Midland and Scottish Railways advertises a range of services for holidaymakers. There are trains leaving to the Midlands and the North every Saturday and Sunday. These are offered with a flexible return ticket, that can be used for 17 days after the initial trip. This implies that travellers are expected to be using the train for a holiday of a week or two. Those travelling to Birmingham and environs can benefit from a tour of the Cadbury chocolate factory at Bournville – an attractive holiday outing which shows the railway collaborating with a large company to offer a package deal. Those who cannot afford to travel far of be away from home long are invited to consider a day-trip to Wembley Stadium for ‘Ice Hockey, Skating & Greyhound Racing’.

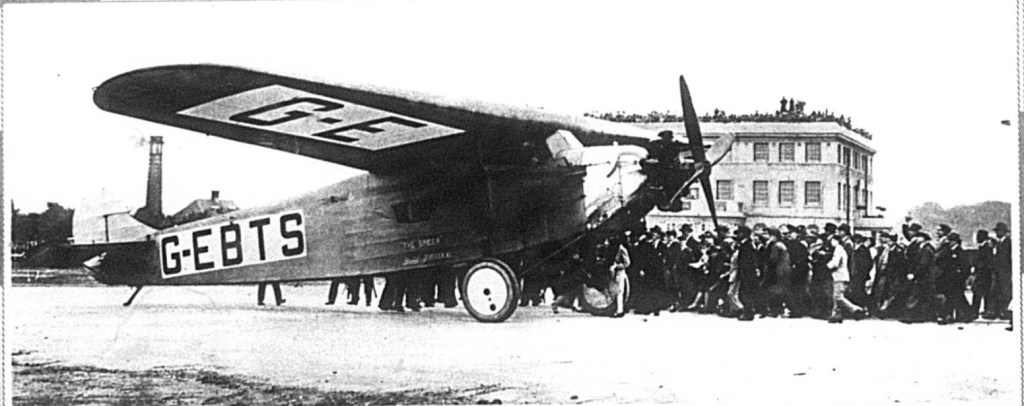

At the top end of the social scale, foreign travel was a possibility. Tourist guides and travel agencies had been available since the 19th century, taking much of the organisation and guesswork out of foreign travel. Commercial flight routes greatly developed during the interwar period, providing a faster way to travel in addition to overland routes and travel by ship. For those who opted for comfort and style over speed, luxury ocean liners and overnight rail journeys through Europe with the Compagnie des Wagon-Lits were good options.

Whether it was to have fish and chips at the seaside or a five-course meal in a dining carriage, throughout the interwar period there was an increased agreement that Londoners should be able to leave the city every now and then and enjoy relaxation and a change of scenery. For many, however, these trips remained limited to single-day outings, as there was little provision for paid holidays and most people could ill afford to take unpaid leave and were at risk of losing their jobs if they did so.

[1] Michael John Law, ‘Charabancs and social class in 1930s Britain’, The Journal of Transport History, Volume 36, No. 1 (June 2015), 45