This is the fourth in a 11-part investigation into the 1934 ‘Bow Cinema Murder’. You can read all entries in the series here.

When John Stockwell decided to attack and rob his employer, he was living as a lodger with a local East End family. He had met Eliza Roake, the head of the family, through the charitable activities she undertook for her Church. After John lost his place in the Salvation Army Boys Home after being convicted of theft, Ellen took him in. After the events of 7 August 1934, their association with John drew this poor but respectable family into a police investigation and a tabloid press sensation.

Ellen Eliza Roake was born Ellen Hoare in 1876; when she was 26, she married Henry George Roake who was five years her junior. The couple had five surviving children: Nellie, born in 1903; William, born in 1906; Eva, born in 1909; Frederick, born in 1913; and Violet, born in 1915. In addition, there were at least two other sons who did not survive past early childhood. All the children were born in Bromley-by-Bow, where Ellen and Henry settled after their marriage. Henry worked as a railway porter in nearby Liverpool Street Station.

In 1926, Henry passed away; five years later, William and Eva both married and moved out of the family home on Empson Street in Bromley. The space that was freed up by their departure is perhaps one of the reasons why Ellen felt able to invite John Stockwell to move into the family home in early 1932.

The Empson Street house was considered small even at that time; the police inspector investigating the murder of Dudley Hoard commented on the house’s small size in one of his reports. There was only one bedroom, which Ellen shared with Nellie and Violet. Beyond the bedroom, there were no other rooms on the house’s first floor. The ground floor consisted of a sitting room, kitchen and scullery. John and Frederick had to make up their beds in the sitting room floor every night. The toilet was attached to the back of the house and needed to be accessed through the garden.

Nellie Roake, who was around 30 at the time of the murder, worked as a ‘chocolate finisher’ in Millwall, an adjacent neighbourhood. The manufacture of chocolates and sweets was an industry that typically employed women, who were believed to be better suited to the detailed work. In addition to her job, Nellie also took care of part of the household chores including cooking meals. She was engaged to William Hilsdon, a labourer who lived around the corner from the Roakes with his parents. William was also born in Bromley; also had a number of siblings; and his parents were also working-class. Although he and Nellie moved in together (with William’s mother) some time in the late 1930s, they did not get married until 1953, after Ellen Roake passed away. There does not appear to have been any bad blood between Ellen and William, however; on the night before the murder on Dudley Hoard in 1934, William spent the evening at the Roake’s house playing cards with the family until nearly midnight.

Unlike his elder sister, Frederick Roake appears to have provided less support to the family. At the time of the murder, he was unemployed due to a knee injury for which he was receiving outpatient treatment at St Andrew’s hospital, where Maisie and Dudley were also taken after the attack. Beyond that, Frederick seems to have spent considerable time loafing around the neighbourhood; he was able to immediately go over to the cinema once news of the attack broke. Frederick and John were not friendly; after John’s arrest, Frederick reported that he usually did not have ‘a lot to say’ to the other man. Despite sharing a bed together every night, the pair appear to have tried to avoid one another as much as possible. Frederick had a girlfriend, Henrietta, who was also born locally. They married in 1938 and stayed in the East End, where Frederick ended up working as a transporter of goods on horse cart.

Violet Roake was the youngest of the family, and the one most closely involved with John Stockwell. They were of the same age, and had been going out from around 1931, when they were both 16. Violet worked as a biscuit packer in a Bethnal Green factory; for many young working class women, light factory work had replaced domestic service as the career of choice. Every morning, John walked Violet to the bus stop around 7.30am. Her shifts started at 8am and finished at 6pm. Because John’s hours at the cinema did not finish until 11pm, most days the only time they had together was that half hour in the morning. The exception was Tuesday, when John was off work and they could do something in the evening. If they were at home, it was likely that there were other people around, and the small size of the house would have afforded them no privacy.

Until the murder, Violet had assumed that she and John would be getting married some day. She eventually married a naval officer in 1939 and moved down to Portsmouth with him. They had a son in 1939 and a daughter in 1949. Unlike most other participants in this story, Violet left the East End definitively when she was in her early twenties. It is possible that her association with a murderer, however unwitting, left a lasting mark on her reputation in the local area.

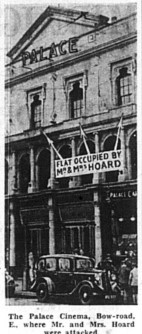

The Roakes were a typical East End family, with blue collar jobs, little money, a small living space, and a lot of family and friendship ties to the local area. Despite their small house, Ellen invited John to live with them when he became homeless, which speaks to her civic-mindedness. If it had not been for their involuntary involvement in the story of the Bow Cinema murder, they would have been absorbed in history without a trace. The case no doubt had a lasting impact on Violet in particular, whose expectations for her life were radically changed as a result of the case. As part of the fall-out, the family were exposed to police investigators, which came onto the scene within minutes of the crime being discovered. The next blog post will unpick who got involved in the police investigation, and how they approached the East End community in which the crime had taken place.