This is the eight in a 11-part investigation into the 1934 ‘Bow Cinema Murder’. You can read all entries in the series here.

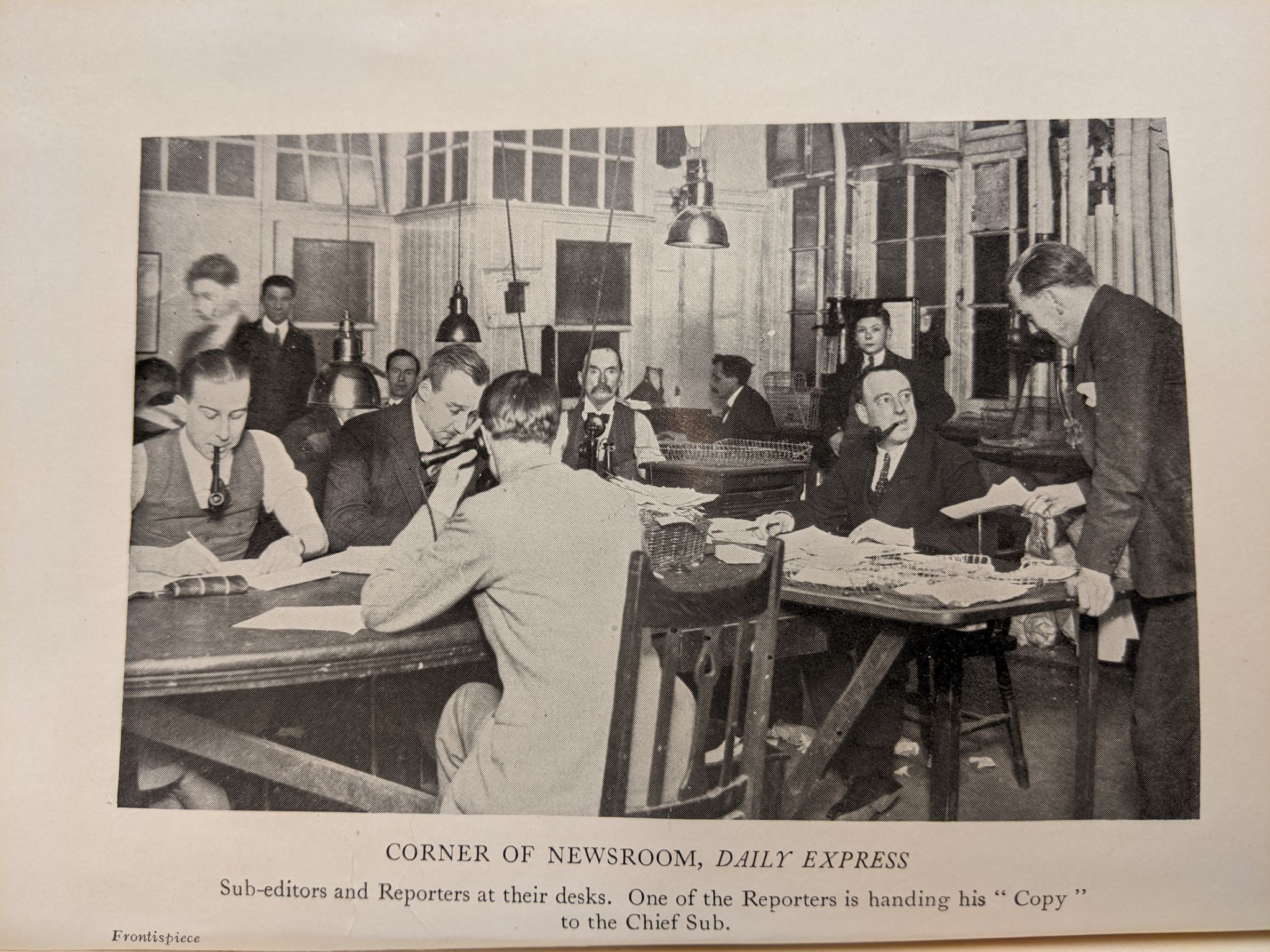

As alluded to in previous instalments in this series, the Bow Cinema Murder was heavily reported on in the popular press. The murder itself was brutal enough; but the fact that a nation-wide man-hunt was called for the prime suspect, and that it took several days to locate and arrest John Stockwell, gave the press irresistible material. The press quickly framed the events in a recognisable narrative format, featuring colleagues and acquaintances of John Stockwell as an ensemble cast of characters. Although the initial press interest culminated with Stockwell’s arrest in Yarmouth on 11 August, and return to London the next day, journalists continued to report on the case as it started to progress through the legal system. Stockwell himself changed from a mysterious figure to a named suspect who could be interpreted through his appearances in court.

As I have described previously on this blog, interwar newspapers reported on court cases on a daily basis, and the reporting conventions in this area provided the reading public with a framework through which to understand criminal and deviant behaviour. The reports on the Bow Cinema Murder both worked within these established conventions and further contributed to them.

In 1934, as today, the English justice system had two ‘tiers’ of courts: the police or magistrate courts, which dealt with minor crimes, and the crown court, which considered more serious crimes. Cases at the crown court were decided by a jury; at the lower court a magistrate heard the case and decided the outcome. Unlike today, however, all cases had to first be heard in the police court, where a magistrate would establish the facts of the case. He would then formally decide whether a case should be referred to the crown court to be heard by a jury. Also unlike today, proceedings in the police court started almost immediately upon arrest, and as the name implied, the majority of the evidence heard was provided by the police officers who had investigated the case and made the arrest.

In the case of the Bow Cinema Murder, Inspector Fred Sharpe played a key role in the magistrate court proceedings. Already during the early stages of the investigation, whilst he and his men were tracking down John Stockwell, they were also ensuring that they had sufficient evidence to put the case forward to trial. The police inspectors continued with this after Stockwell’s arrest – (re)interviewing witnesses to ensure that there were no gaps in their narrative that could be exploited by the counsel for the defence.

Stockwell made his first appearance in the Thames Police Court on 13 August, only two days after his dramatic arrest in a Yarmouth hotel. That was a Monday, and from then on the case was heard weekly on Tuesdays until 18 September, when Stockwell was formally committed to trial at the Old Bailey. All of these hearings were reported on in the national press. The reports were standalone articles, outside of the regular ‘today in court’ columns. This underlined the relative importance the press gave to this particular criminal investigation, which was set apart from the daily churn of magistrate court proceedings.

Stockwell’s appearance in court gave reporters the first opportunity to have a good look at him. Although the attack on Dudley Hoard was described as ‘A murder as grim and mysterious as any enacted on [the Eastern Palace Cinema’s] flickering screen’[1], its alleged perpetrator was repeatedly described as quiet, ‘very pale’ and even physically weak.[2] The Daily Mirror went further than most in describing Stockwell as ‘a young man of medium height, with wavy blonde hair, and as he faced the magistrate he stood with his hands clasped behind his back and started straight in front of him.’[3] The reference to ‘wavy blonde hair’ makes Stockwell akin to a romantic hero. He was also noted to be wearing an open-necked shirt and tennis shoes – hardly the outfit of a killer. At the end of the proceedings Stockwell was reported to have asked ‘in a quiet voice’ for leave to see his girlfriend and some other friends.

Even more than John Stockwell’s hair and clothes, newspapers made repeated references to his young age – he was only 19 at the time of the murder and trial. His age usually appeared with the first line of every article about the case. The Daily Mail landed upon the description of him as a ‘lad’.[4] Multiple headlines in the paper referred to the ‘Cinema Lad’ throughout his arrest and trial. ‘Lad’ provides a compromise between ‘man’ and ‘boy’: it refers to Stockwell’s relative youth without suggesting that he should be tried as a juvenile.

The police court proceedings heard evidence of Inspector Sharpe, setting out week by week the case against Stockwell. He first established that Hoard had been murdered; and then that Stockwell had made a full confession to him in the drive back from Yarmouth. The court was also presented with a letter which John Stockwell had sent to Lowestoft police, when he was attempting to fake his own death through suicide. This letter contained another confession of the murder. The people Stockwell interacted with in Lowestoft and Yarmouth were called to give their evidence, as was Sir Bernard Spilsbury, who had been involved in the autopsy of Dudley Hoard.

At the final hearing, Violet Roake, John Stockwell’s one-time girlfriend, was called to testify. Stockwell had written her a letter while he was in Lowestoft, claiming that he was not guilty but also asking her to call him by a different name going forward.[5] Although Stockwell had been granted permission to receive visits from Violet, it appears that she had retained her distance from him; the Evening Standard reported that Violet did not look at Stockwell when she entered court.[6]

Although the police court hearings had given the press and public a first overview of the details of the murder and manhunt, they were considered a preliminary to the inevitable referral of the case to the Crown Court. There, at the Old Bailey in central London, the real drama of the case was expected as a jury of twelve men and women had to decide whether John Stockwell was guilty of murder – and a guilty verdict would automatically lead to a death sentence.

[1] ‘Midnight Murder in a London Cinema’, Daily Mail, 8 August 1934, p. 9

[2] ‘Stockwell Accused of Cinema Murder’, Evening News, 13 August 1934, front page; “I did not mean to kill Mr Hoard”, Daily Mirror, 14 August 1934, p. 8

[3] “I did not mean to kill Mr Hoard”, Daily Mirror, 14 August 1934, p. 8

[4] For example: ‘Cinema Lad Found’, Daily Mail, 11 August 1934, p. 9; ‘Cinema Lad in Court’, Daily Mail, 14 August 1934, p. 10

[5] ‘Cinema Tragedy’, Daily Mail, 19 September 1934, p. 6

[6] ‘Girl’s Talk on Crime with Stockwell’, Evening Standard, 18 September 1934, p. 12