Journalism boomed during the interwar period – the British were avid newspaper readers: its post-war newspaper consumption per capita was the highest in the world.[1] The increased popularity of newsprint fuelled the demand for more journalists – by 1938 there were an estimated 9000 people working as journalists in Britain.[2] The often glamorous depiction of journalists in novels, autobiographies and (Hollywood) films, plus the fact that there were no formal entry requirements to the profession, made journalism an appealing potential career path.

As has been covered elsewhere in the blog, a formal University Diploma for Journalism launched at the University of London after the First World War. Additionally, there was a flourishing market of self-help books aimed at teaching novices how to become professional writers. The University qualification, however, was not accessible to many people as it was only taught in-person in London and required entrants to have matriculated (i.e. passed a University entry exam). Self-help books required substantial self-discipline on the part of the aspiring journalist. It is no wonder, then, that a third potential route into journalism gained popularity: attendance at a non-accredited ‘School of Journalism.’

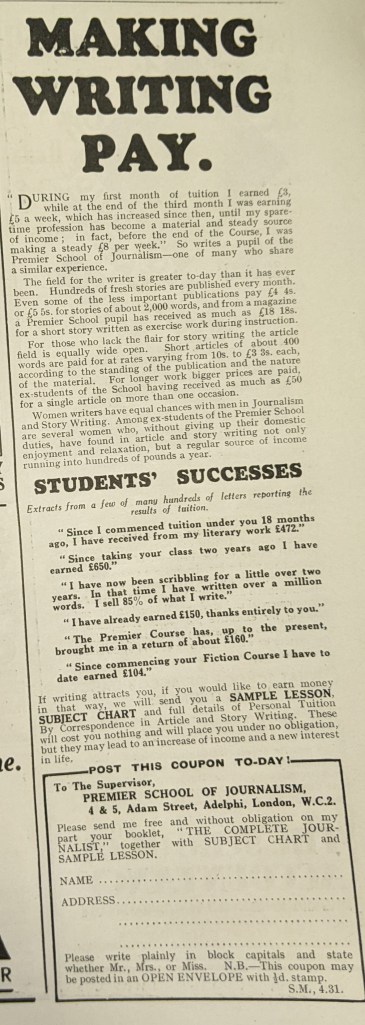

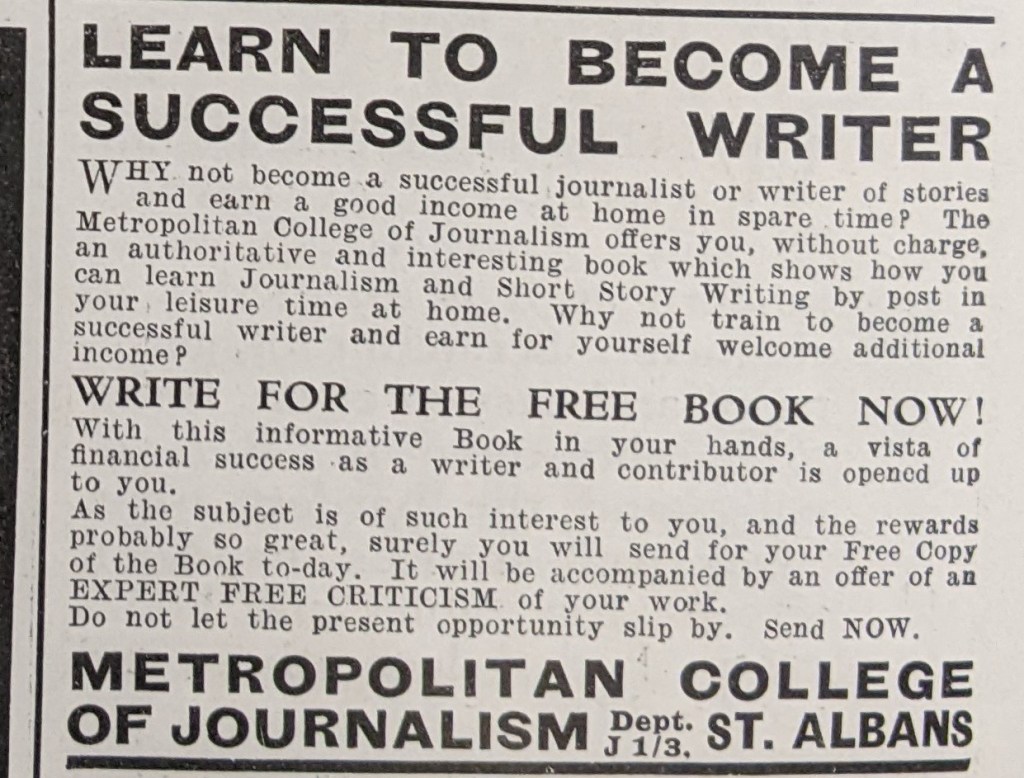

There has not been any historical research published on the phenomenon of ‘schools of journalism’, but my own research indicates that they started up immediately after the First World War, and that in a short space of time many different establishments were formed. A single issue of The Strand Magazine, a monthly publication of fiction short stories and non-fiction pieces, contained adverts for the Premier School of Journalism (‘Making Writing Pay.’), the Metropolitan College of Journalism (‘Learn to become a successful writer’) and The Regent Institute (‘Free Lessons for New Writers’). These schools all offered potential clients an easy route into a remunerative writing career. As the advert for the Metropolitan College posed: ‘Why not become a successful journalist or writer of stories and earn a good income at home in spare time?’

Most Schools of Journalism offered a variation of the same: a correspondence course in which students could submit their trial articles, which would then be corrected by tutors and sent back to students with constructive feedback. After a set period of study, students were promised that their writing would be good enough to sell. The advert for the Premier School of Journalism includes (alleged) testimonials of former students quoting significant financial gains from their work: ‘Since taking your class two years ago I have earned £650’ and ‘Since I commenced tuition under you 18 months ago, I have received from my literary work £472.’ For comparison, the minimum weekly pay for a staff journalist in the early 1930s was just shy of £5 – and that was a considerably better wage than journalists had been paid before the National Union of Journalists pushed for national pay agreements.[3]

The aggressive advertising of these journalism schools caused considerable anxiety and disgruntlement for members of the NUJ, who were either worried that these schools would lead to a surplus of journalists and therefore a competitive job market; or felt that these schools were scams designed to make money off unsuspecting people. One of the first schools to launch after the First World War was The London School of Journalism (which still operates today). It was founded by novelist Max Pemberton and it ran a prominent advertising campaign in the national press. In August 1920, NUJ member and journalist John Ramage Jarvie argued that this advertising campaign must have cost the School a significant amount; and that as the fees they charged students were modest, the School’s operating model must rely on recruiting a high volume of students in order to make a profit. Jarvie therefore considered it inevitable that businesses like the LSJ would increase unemployment amongst journalists by flooding the market.[4]

The NUJ initially did not pick up on its members’ concerns about the LSJ and similar ventures, and gave Max Pemberton a platform to advertise his school to NUJ members. Pemberton stated in an article for the Union monthly newsletter that his school actually told many potential students that journalism was not the right career for them. He presented his initiative as a sort of gatekeeper for the profession, and argued (rather disingenuously) that the School’s adverts did not explicitly promise to turn students into journalists.[5]

Pemberton’s arguments failed to convince the NUJ membership, and the Union’s executive swiftly decided that they would only provide advertising space to training initiatives aimed at current, working journalists. Nevertheless, the schools continued to do business throughout the interwar period. Journalist Harold Herd described how he set up his own school in the late 1910s, which was still trading by the time he wrote his memoir in 1936. Like Pemberton, he argued that he only took on students who had a chance of making it as a professional journalist: ‘Every year we reject hundreds of people on the ground that they do not reveal sufficient promise to justify a recommendation to enrol.’[6]

Despite the protestations of school founders, the sheer volume of such organisations; their modest tuition fees; and the simplicity of their teaching materials (one correspondence course mainly encouraged students to learn from, and copy, existing writers’ work) suggest that it is unlikely that many of their students found professional success. Despite there being no formal entry requirements to becoming a journalist, these unregulated schools sold a dream of easy earnings which could not become a reality for most of their pupils.

[1] Adrian Bingham, ‘‘It Would be Better for the Newspapers to Call a Spade a Spade’: the British Press and Child Sexual Abuse, c. 1918–90’, History Workshop Journal, vol. 88 (2019), 91

[2] Political and Economic Planning, Report on the British Press (London: PEP, 1938), p. 13

[3] A.M. Carr-Saunders and P.A. Wilson, The Professions (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1933), p. 268

[4] J.R. Jarvie, ‘The London School of Journalism LTD’, The Journalist, August 1920, p. 68

[5] Max Pemberton, ‘The London School of Journalism LTD’, The Journalist, October 1920, p. 90

[6] Harold Herd, Press Days and Other Days (London: Fleet Publications, 1936), p. 124